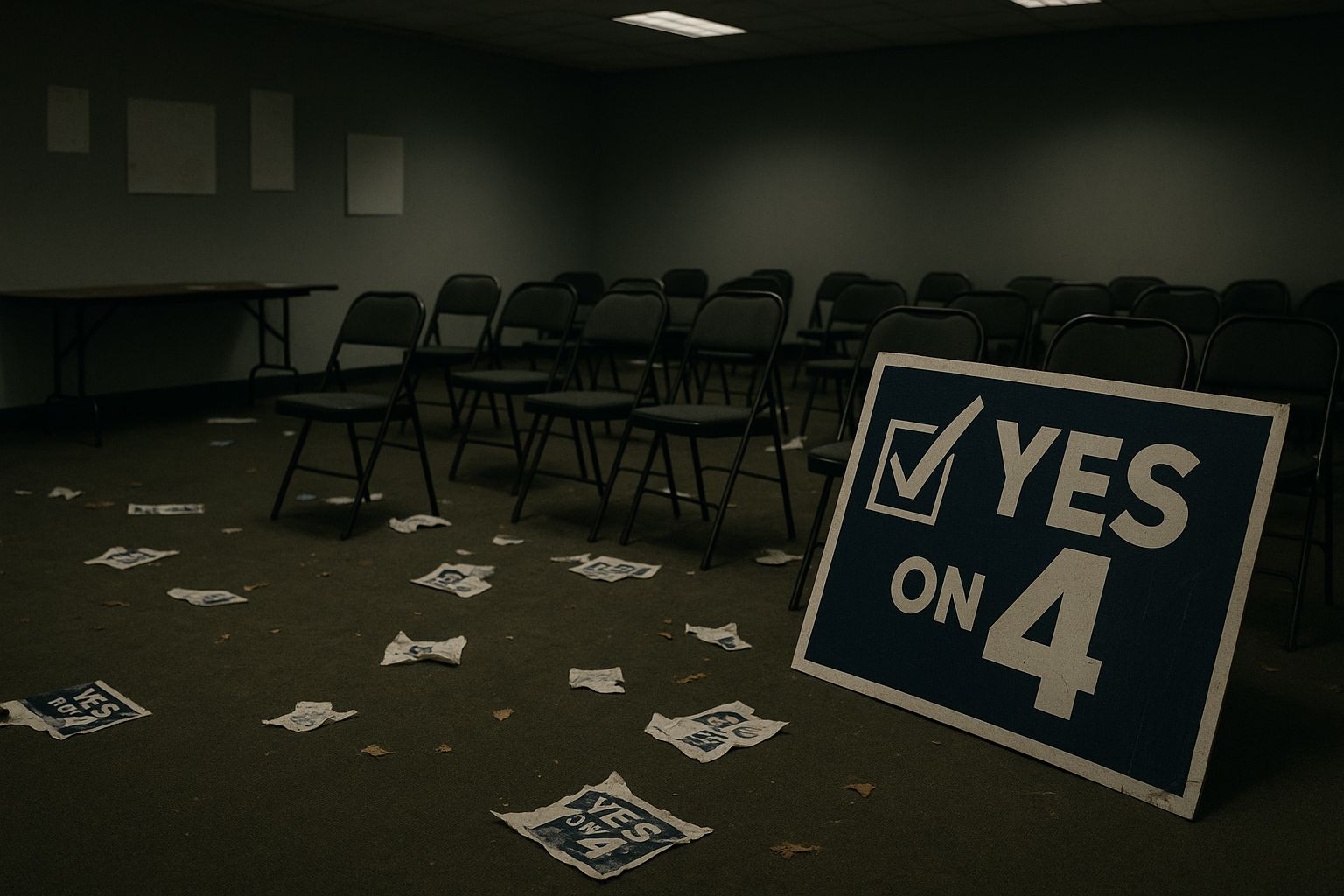

Why the Question 4 Campaign Fell Short, Part 7

7. The Campaign Possibly Put Its Grassroots Staff and Nonprofit Affiliates in Legal Jeopardy

By Graham Moore

WHY THE CAMPAIGN FELL SHORT

The list of problems with the Question 4 campaign is long, and this postmortem will examine the major issues in depth one by one.

Part 1 (released on October 17, 2025) analyzes the decision to run a policy out of touch with public opinion as indicated by polling, against the recommendations of the Dewey Square Group strategists hired by the campaign and the Massachusetts ACLU.

Part 2, initially released in installments as Part 2.1, Part 2.2, and Part 2.3 (on October 21, October 31, and November 6, 2025), analyzes the campaign’s costly handling of a polarizing psychedelics activist and underground practitioner.

Part 3 (released on November 8, 2025), analyzes the campaign’s decision to divert resources to a new nonprofit, co-founded by a close associate of Yes on 4’s campaign director, while polling behind.

Part 4 (released on November 17, 2025), analyzes the campaign’s decision to portray itself as led by a local female veteran who had suffered PTSD while the official campaign director was a non-veteran, white male, with no history of serious mental illness, operating from 3000 miles away in California and patient advocates were excluded from the strategy team.

Part 5 (released on December 7, 2025), analyzes how the campaign’s messaging exaggerated the risks of its proposal and capitulated to misleading ballot language—in contradiction to the campaign’s own polling and research.

Part 6 (released on December 26, 2025), analyzes a variety of the campaign’s shortcomings in the context of an organizational structure that discouraged accountability.

WHY THE CAMPAIGN FELL SHORT

7. The Campaign Possibly Put Its Grassroots Staff and Nonprofit Affiliates in Legal Jeopardy

A Professional Imperative

In 2025, as reported by the Boston Globe and Lucid News, I filed complaints with Massachusetts’ Office of Campaign and Political Finance (OCPF) regarding possible violations of campaign finance law related to Yes on 4. I did so only after a conversation with an attorney produced concern that certain payments to Jamie Morey and me for our campaign work might not have been properly disclosed.

As someone deeply invested in the future success of psychedelic policymaking, I had been reviewing Yes on 4’s public financial data to better understand the reasons for the campaign’s loss. And I had subsequently discovered there was no record of the post-election bonus compensation paid to Morey and me in the ballot committee’s disclosures to the OCPF.

While I am now represented by an attorney at Considine & Furey, I employed an attorney currently serving on Massachusetts’ State Ethics Commission—“an independent state agency that administers and enforces the provisions of the conflict of interest law and financial disclosure law” according to mass.gov—during spring 2025 to help me understand to what degree Morey and I could be in legal jeopardy. Based on the documentation I shared with him and my descriptions of what occurred during the campaign, the attorney informed me there was possible legal jeopardy for me (and Morey by extension) as well as the ballot committee and certain nonprofit affiliates, particularly veterans charity Heroic Hearts Project. He also told me it was “very unlikely” I would be charged for my conduct, even if regulators determined I had likely engaged in illegal activity, so long as I was “on the side of the government” (i.e. was honest and transparent with state regulators). My takeaway from that conversation was that Morey and I would be safest from a reputational and legal standpoint by fully and transparently disclosing everything we knew related to possible violations of campaign finance law to the appropriate regulatory authority, the OCPF. And that was what we did.

I also asked the attorney whether Morey’s and my post-election legislative advocacy violated Massachusetts lobbying laws. Despite several ballot committee colleagues being registered lobbyists and rhetorically supporting our efforts to get psychedelics bills filed, none had warned Morey and me about strict regulations that could have resulted in us being fined tens of thousands of dollars each in addition to harming our reputations. The attorney concluded we had not met the criteria for mandatory registration and thus faced no lobbying violations—leaving campaign finance as our only potential jeopardy.

The risk of us being wrapped up in a probe eventually, whether we came forward or not, was more than theoretical. Possible violations of campaign finance law are routinely reported to the OCPF, and the OCPF regularly conducts investigations. Illustrating the point, Yes on 4’s campaign manager and ballot committee chair Danielle McCourt filed a complaint with the OCPF about the opposition to Question 4 on October 7, 2024, as reported by State House News. McCourt’s complaint “[requested] a review of a potential violation of the Massachusetts Campaign Finance Law reporting” and pointedly concluded: “transparency is paramount to election integrity and a cursory glance at the facts suggests information may be being withheld.”

The same article that reported on McCourt’s filing reported that the opposition committee, the Coalition for Safe Communities, had sent a cease and desist letter “to TV stations alleging that a Yes on 4 ad did not ‘include a proper disclaimer’ about top campaign contributors nor refer viewers to OCPF's website.” Especially considering the attorney indicated to me that payments for Heroic Hearts Project television advertisements may not have been properly disclosed, the fact Yes on 4’s advertising in particular had already been the focus of scrutiny and legal action—amidst a political tit for tat—suggested it was a real possibility an investigation was already underway.

Both as advocates and as professionals, Morey and I were closely and openly affiliated with the Question 4 campaign. In addition to our operational leadership roles, we had been the post-election wind down co-executive directors of the ballot committee, during which time we directed a successful effort—involving lawmakers and community members—to get a record number of psychedelics bills filed. To preserve our effectiveness as leaders, it was paramount we not be complicit in possible major financial impropriety on the part of the organization we once nominally led (our theoretical authority as co-executive directors, similar to that of Emily Oneschuk as grassroots campaign director, was mostly disregarded by our senior colleagues). Especially considering the details of our bonus payments, which were paid by the Heroic Hearts Project, the possible reputational damage of staying silent could be severe—at worst, we could be accused of knowingly defrauding a veterans charity of thousands of dollars. By self-reporting to the OCPF, and then coming forward publicly, we took the course of action best aligned with our values and goals.

Giving us additional confidence was the knowledge the OCPF is not draconian. Neither of us had any interest in former colleagues being possibly frog-marched to prison or fined into oblivion. Our understanding was that, even if the OCPF determined there had been violations of campaign finance law, the most likely outcome would be relatively minor fines for involved entities and additional financial disclosures. The largest fine the OCPF had ever imposed was $426,466, and that was in response to over $15,000,000 in improper donations—we were confident that even the worst case campaign finance scenario for Yes on 4 involved nowhere near that scale of money. More recently, the OCPF fined a ballot committee just $4000 on account of it not reporting $2,300,000 in contributions on time. Our hope was that, if the OCPF identified improperly disclosed financial activity by Yes on 4, it would force transparency that would encourage more politically effective resource allocation moving forward—without causing undue harm to any individuals or organizations involved. And, in the case there had not been any violations of campaign finance law, it would be relatively easy for investigated parties to exculpate themselves.

A Pattern of Concern

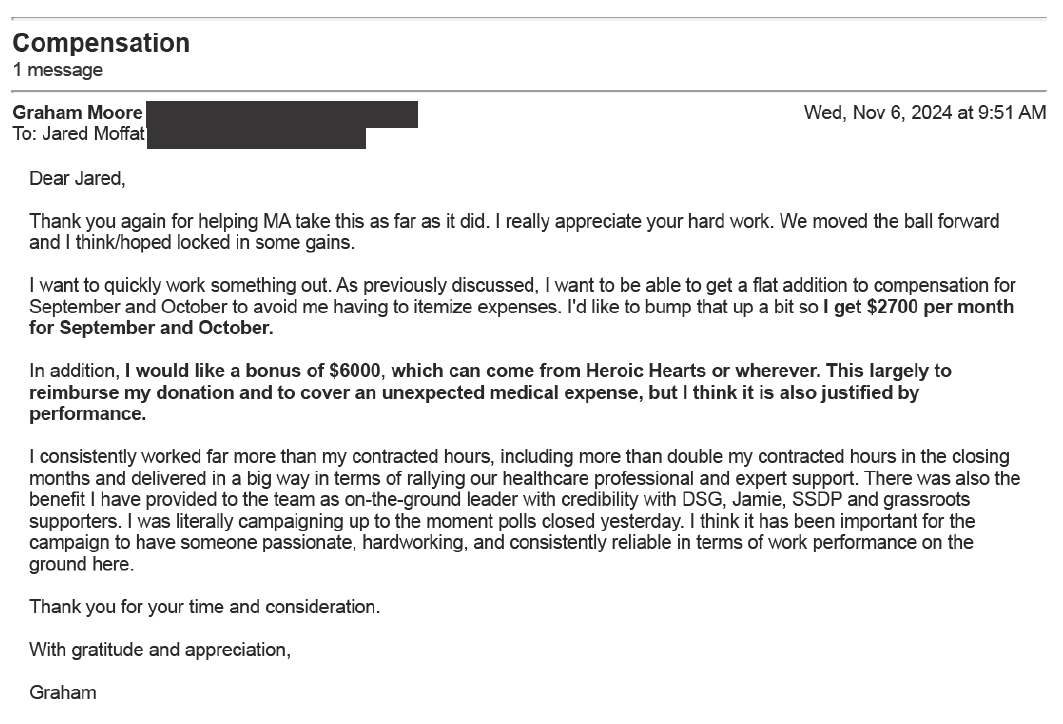

The possible violations of campaign finance law most directly concerning me and Jamie Morey were related to our bonuses. In 2024, Morey and I both requested additional compensation for our campaign work, which was assented to. In my case, I had requested “a bonus of $6000 […] justified by performance” from Yes on 4 campaign director Jared Moffat the morning after the election in an email, displayed below.

I noted the bonus “[could] come from Heroic Hearts or wherever.” This was because I was aware Moffat had offered to have Heroic Hearts Project pay for Morey’s bonus. Nonprofits like Heroic Hearts Project are allowed to cover campaign expenses, including compensation for staff, in the form of in-kind contributions, so this was not untoward. In subsequent text messages, shown below, Moffat acknowledged receipt of the email and agreed to the bonus being paid from Heroic Hearts Project, with my consent. I referred to the bonus as “an in spirit bonus/refund of donation” in a text message because I thought of it largely as a refund of my $5000 donation to the ballot committee.

According to my attorney in spring 2025, this equivocation about whether the money was a refund of my donation or bonus compensation for my performance was potentially problematic—there are different mechanisms for refunding a contribution and for paying a contractor a bonus—but more significant legal risk arose from the combination of the campaign-related payment apparently not being disclosed to the OCPF and certain details of how it was effectuated.

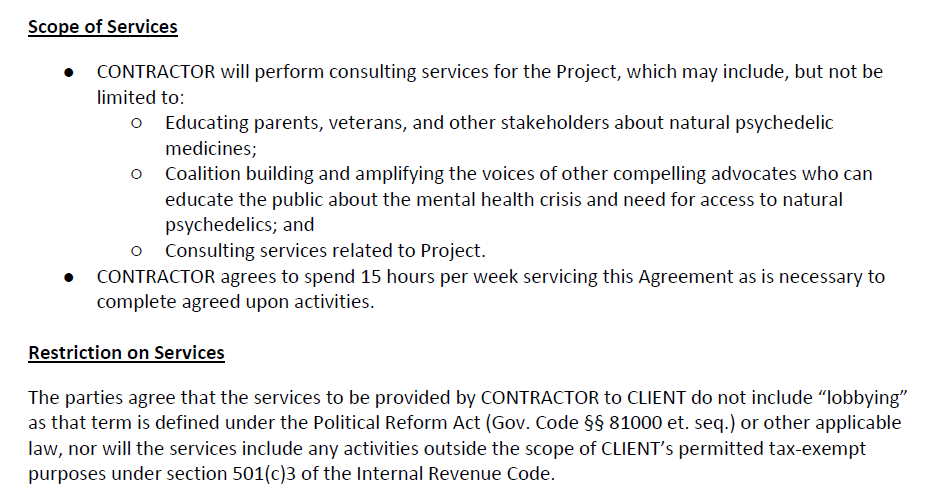

Moffat emailed me a Heroic Hearts Project contract to sign on November 26, 2024, which I signed on December 14, 2024, and the president of Heroic Hearts Project, Jesse Gould, signed on January 13, 2025. In the contract, Heroic Hearts Project agreed to pay “a project fee of $6000”—the precise amount I requested for my bonus—as compensation for a “scope of services” with “restrictions” (see below) that I, the “contractor,” “[would] perform” (see contract excerpt below).

While I signed the contract as if it was a boilerplate agreement to facilitate my bonus, it technically obligated me to perform services for Heroic Hearts Project “for 15 hours per week”—an obligation that was never communicated to me in any other form and that I had no intention of fulfilling. Furthermore, the “restriction on services” within the contract precluded it from compensating “‘lobbying’ as that term is defined under the Political Reform Act […] or other applicable law,” a definition that encompassed campaigning for a ballot question. And while the contract was signed by Gould, and a $6000 payment made to me by Heroic Hearts Project, I never spoke to Gould or to any Heroic Hearts Project employee about the contract or the purpose of the compensation. Had the $6000 been disclosed to the OCPF as an in-kind contribution to Yes on 4 by Heroic Hearts Project, then the simplest explanation would have been I was carelessly given a boilerplate contract to sign with no intent to hide a payment. But the apparent absence of a disclosure—no in-kind or monetary contributions from Heroic Hearts Project to the ballot committee were reported—increased the likelihood regulators would scrutinize the transaction as potentially improper. And I could not be sure that Gould, or anyone at Heroic Hearts Project, was aware of the true reason I had been paid.

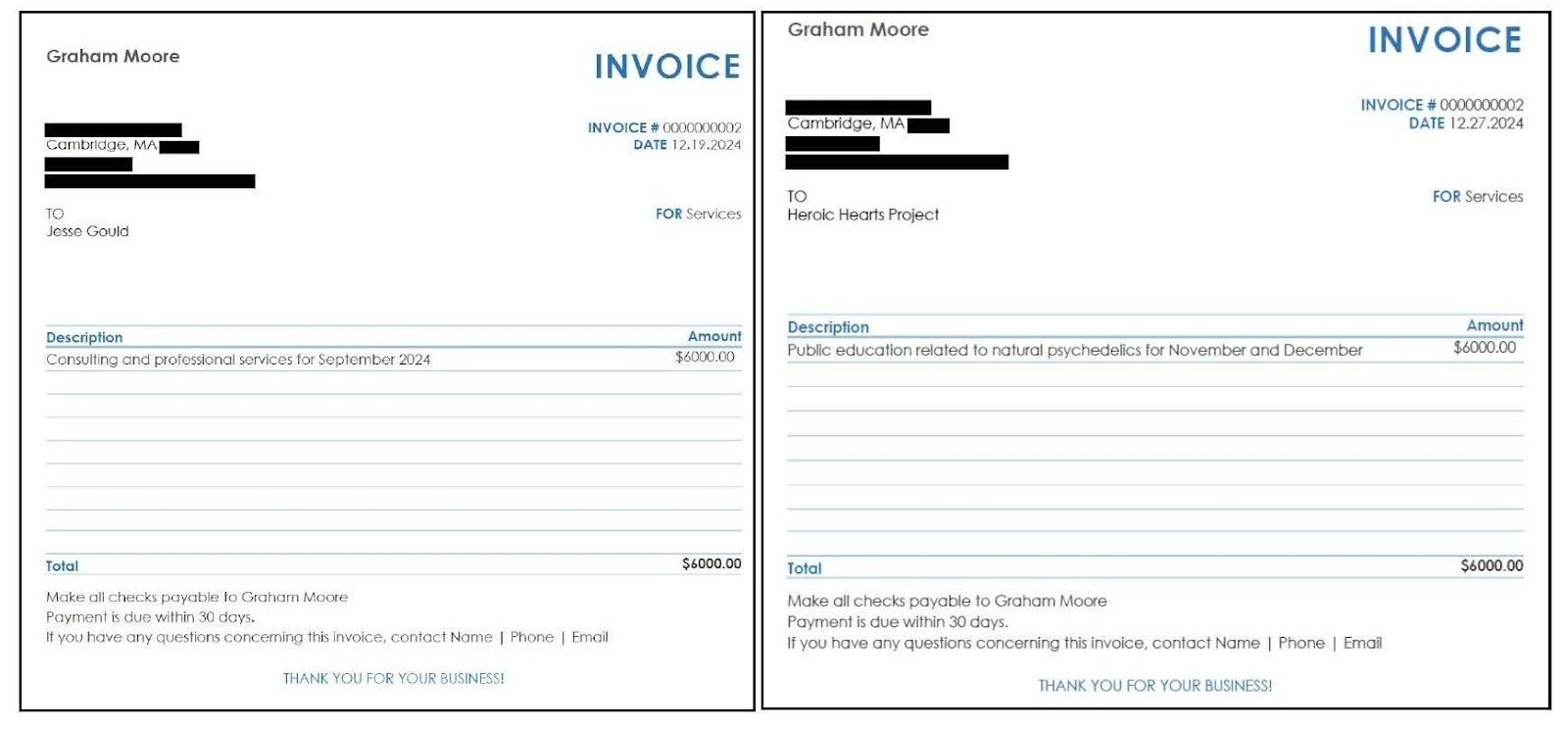

Adding to my possible culpability, I had altered my invoice to Heroic Hearts Project at Moffat’s suggestion. While my original invoice billed Jesse Gould for “Consulting and professional services for September 2024”—firmly within the timeframe of the election—, Moffat instructed me in an email to address the invoice to “Heroic Hearts Project” and to bill for “Public education related to natural psychedelics for November and December” instead, which I did. Below, you can see the two invoices side by side—the original on the left and the revised invoice on the right—above a screenshot of the email thread in which Moffat requests the invoice be changed.

After sending Moffat a third invoice—altered only to include my ACH information—I received $6000 from Heroic Hearts Project in February 2025.

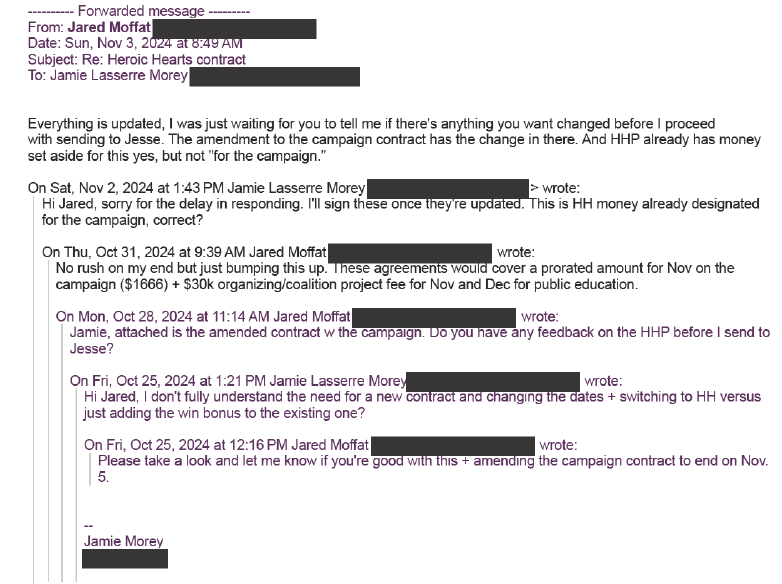

Morey’s experience receiving her bonus was almost identical to mine, including being asked to revise her invoice for Heroic Hearts Project. Morey, however, pressed Moffat over email on why her bonus could not be paid by amending her existing contract with the ballot committee. Although he did not reply to that inquiry over email, when she later asked, “This is HH [(Heroic Hearts Project)] money already designated for the campaign, correct?,” Moffat informed her: “HHP [(Heroic Hearts Project)] already has money set aside for this yes, but not ‘for the campaign.’” This email thread is displayed below.

As reflected in the email thread, Morey’s original contract with the ballot committee, like mine, ran through December 2024. In response to her request for additional compensation, Moffat had proposed amending her ballot committee contract to end after election day—hence the “prorated amount for Nov on the campaign ($1666)” as described over email—and then paying Morey what she was originally owed for November and December 2024, plus bonus compensation, through a Heroic Hearts Project contract—hence the reference to “$30k organizing/coalition project fee for Nov and Dec for public education” in the thread.

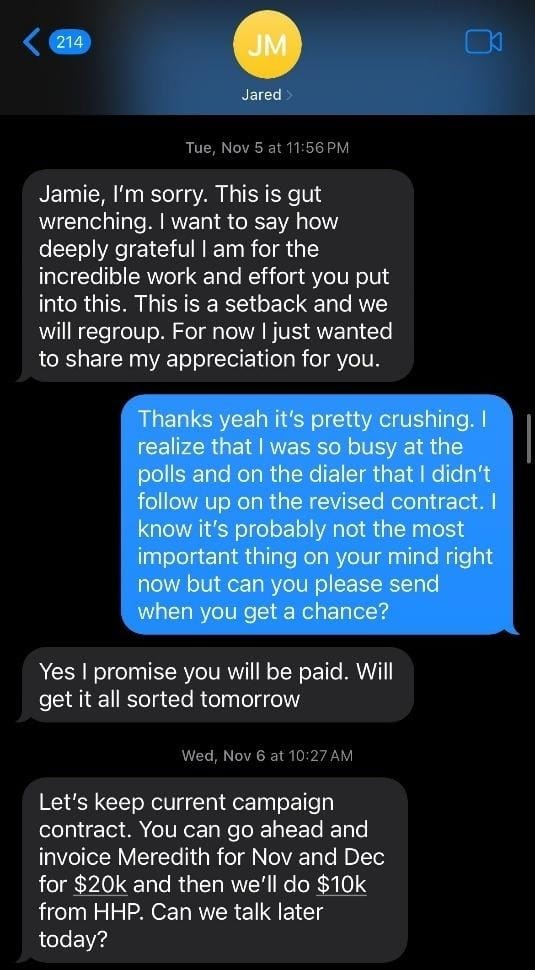

But after the election, Moffat changed his mind, texting Morey, “Let’s keep current campaign contract. You can go ahead and invoice Meredith [Moghimi, the ballot committee treasurer,] for Nov and Dec for $20k and then we’ll do $10k from HHP.”

When Morey subsequently asked, “Why the change on the contract?”, Moffat replied, “We ended up w a little bit extra $ in the campaign w last minute donations.”

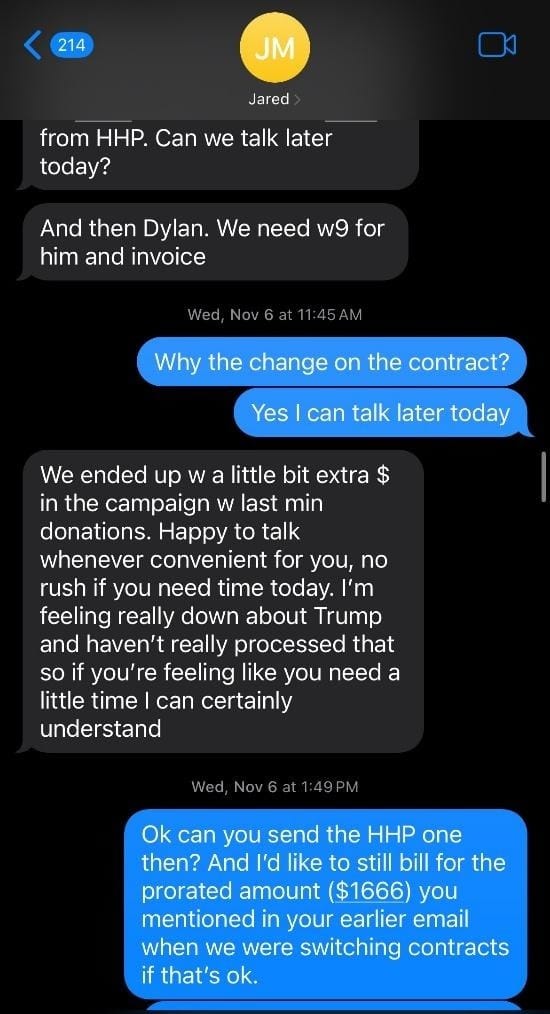

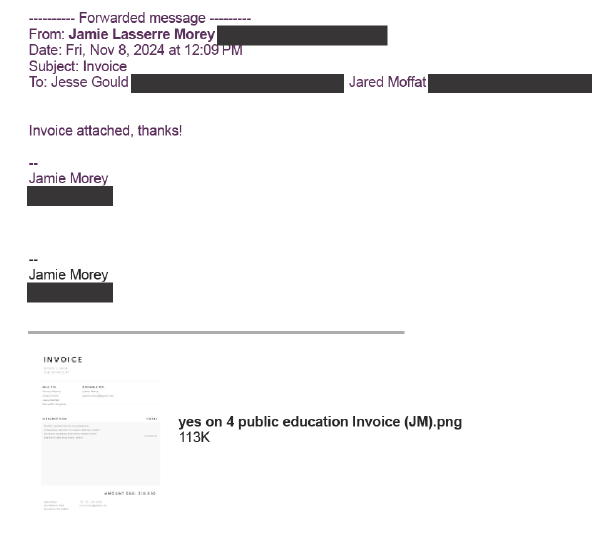

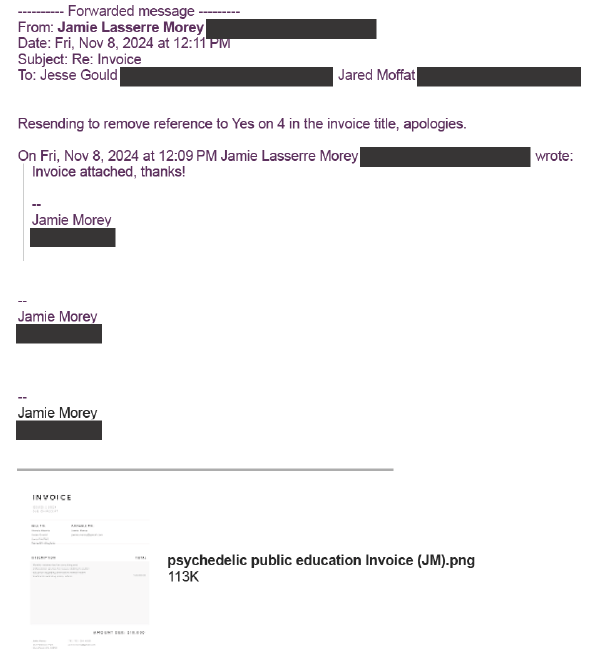

Two days later on November 8, 2024, Morey emailed an invoice with the file name “yes on 4 public education Invoice (JM)” to Moffat and Gould.

In response, Moffat promptly asked Morey to alter the invoice, texting her: “Can you change the title of the invoice, can’t be ‘yes on 4’ Just psychedelic public education.”

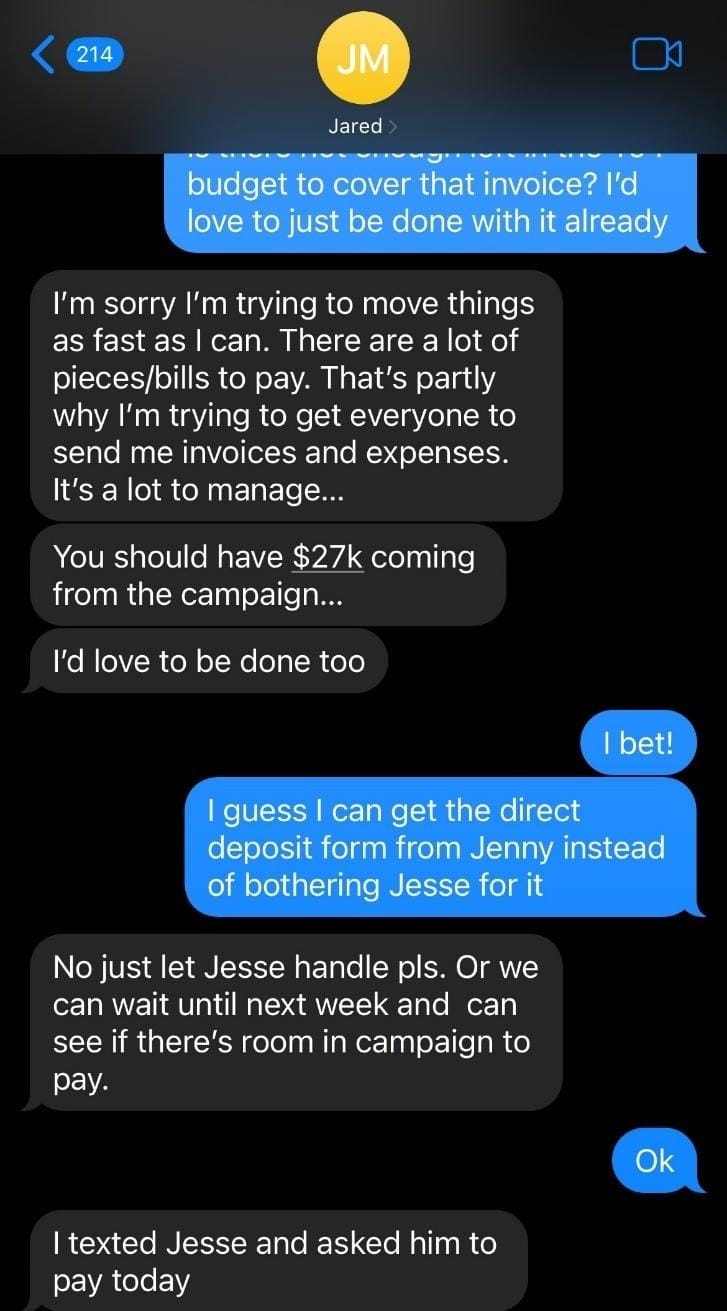

When Morey floated trying to speed up Heroic Hearts Project paying her invoice by reaching out to another individual for a direct deposit form, Moffat pushed back further in the text thread. He asked her to wait for Gould (referred to by his first name “Jesse”) but also proposed another option, sharing: “Or we can wait until next week and can see if there’s room in the campaign to pay.” A little later, he announced he had “asked [Gould] to pay today.”

Consequently, Morey emailed Moffat and Gould a revised invoice, retitled to “psychedelic public education Invoice (JM).”

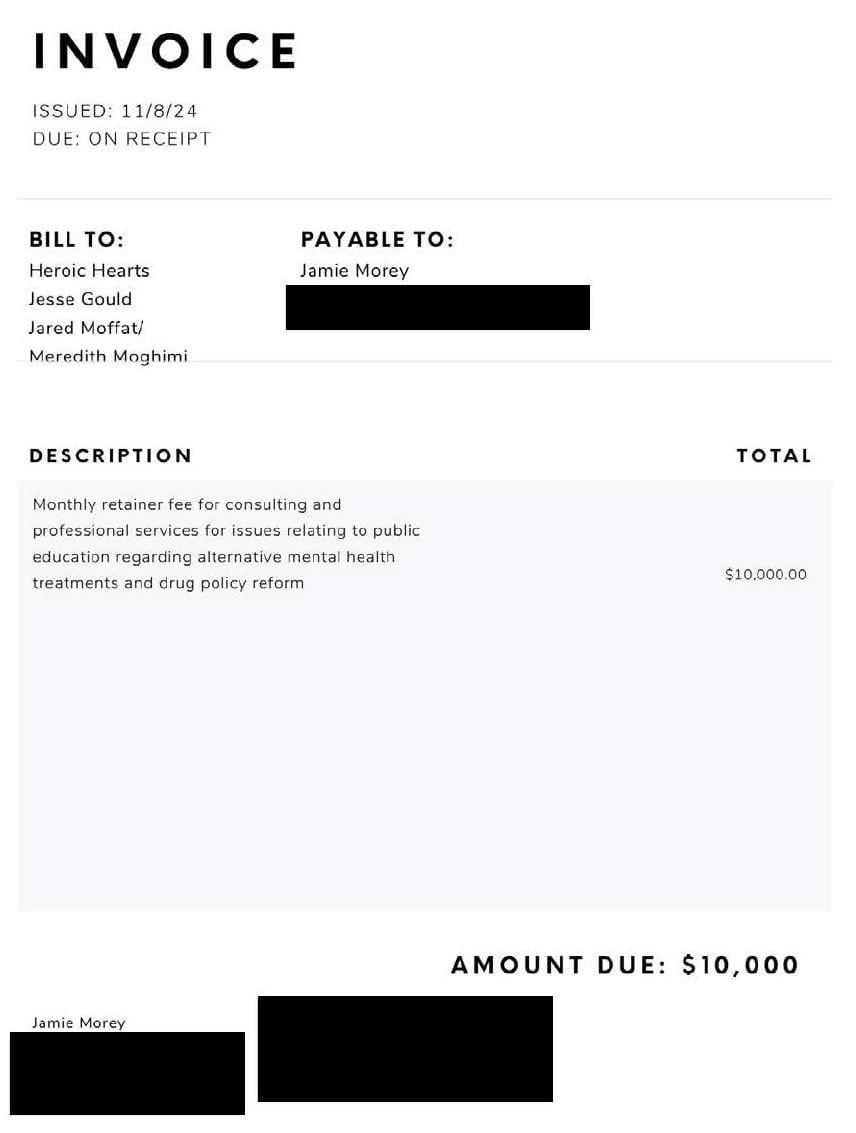

Notably, the final version of the invoice still included ballot committee treasurer Meredith Moghimi and Moffat in the “bill to” section, in addition to Gould and “Heroic Hearts,” and the invoice did not date the services provided, reflecting Morey’s understanding that she was billing for her campaign work.

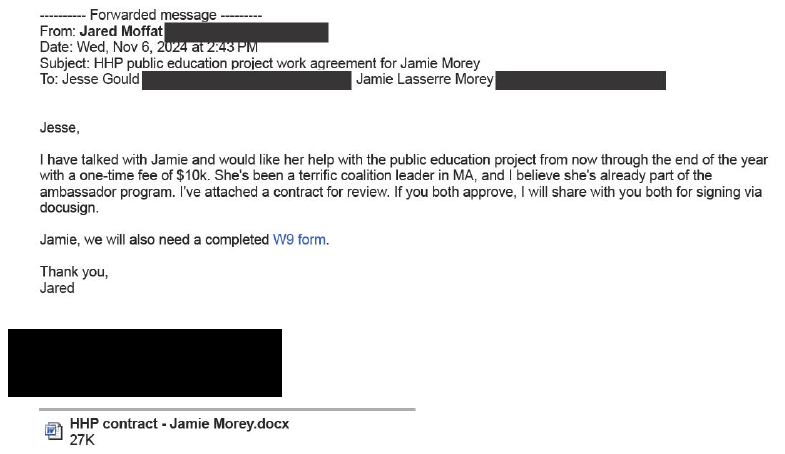

But the Heroic Hearts Project contract Morey signed was the same as mine, with the identical stipulation that the contract did not apply to “lobbying,” i.e. ballot question campaign work. And in an email to Gould and Morey introducing the contract to Gould, Moffat explicitly pitches Morey to “help with the public education project from now through the end of the year,” with no mention of the payment being compensation for Morey’s ballot committee performance.

Morey did not initially read this email and her contract carefully. But, after I alerted her to the issue of potentially undisclosed campaign contributions, Morey realized that she, like me, had taken for granted that Gould and Heroic Hearts Project knew the intended purpose of the payments without actually verifying that was the case. Also like me, Morey had never been instructed by Moffat or anyone else to work on a project for Heroic Hearts Project per the terms of the contract and had not done so, believing the contract compensated her for work already performed for Yes on 4. Moreover, apart from the contract, the invoice title, and the email regarding “the public education project,” all Morey’s communications with Moffat about the money to be paid by Heroic Hearts Project had treated it as practically interchangeable with ballot committee expenditure, hence Moffat explaining that “a little bit extra $ in the campaign w last minute donations” meant Morey did not have to receive as much of her promised compensation from Heroic Hearts Project. My attorney in spring 2024 indicated that the unclear boundaries between ballot committee and nonprofit spending—including but not limited to Morey’s and my bonuses—created potential liability.

A Pervasive Overlap

According to Massachusetts law, “a contribution of money or anything of value to an individual, candidate, political committee, or person acting on behalf of said individual, candidate or political committee, […] for the purpose of promoting or opposing a charter change, referendum question, constitutional amendment, or other question submitted to the voters” is a political contribution subject to mandatory disclosure. What qualifies as “for the purpose of promoting or opposing” is not defined in statute, leaving room for interpretation.

This said, a ballot committee—like that of Yes on 4—under Massachusetts law “may receive, pay and expend money or other things of value solely for the purpose of favoring or opposing the adoption or rejection of a specific question or questions submitted to the voters” and “shall not […] make any expenditure inconsistent with the purpose for which it was organized” (emphasis in italics mine). Accordingly, the greater the involvement of a ballot committee—whose actions are presumed, by default, to be in furtherance of its political goal—in a nonprofit expenditure, the more likely that expenditure will be categorized as a contribution to the ballot committee by the OCPF. As Heroic Hearts Project made multiple, major expenditures that appeared coordinated to some degree with Yes on 4’s ballot committee—while simultaneously reporting no monetary or in-kind contributions to Yes on 4—there was considerable risk state regulators would determine one or more of these constituted an undisclosed in-kind contribution. To my knowledge, the largest portion of these expenditures was for television advertising.

As the Boston Globe reported, Heroic Hearts Project spent at least $317,603 for television advertisements that began running in fall 2024—I was told by Jared Moffat that Heroic Hearts Project spent approximately $500,000 airing a commercial promoting “natural psychedelic medicine therapy.” The evidence of coordination between the nonprofit and the ballot committee regarding this spending includes, but is not limited to, the following information:

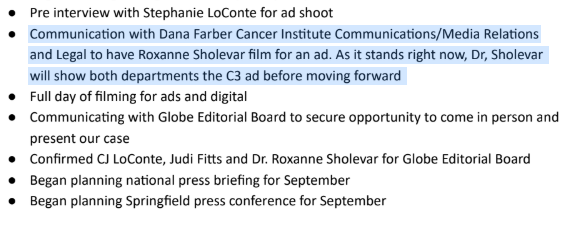

In internal ballot committee reports, the campaign noted communicating with the employer of Dr. Roxanne Sholevar, featured in the Heroic Hearts Project advertisement, to have her “film for an ad.” The campaign also noted: “As it stands right now, Dr, [sic] Sholevar will show both departments the C3 ad before moving forward.” Considering Dr. Sholevar was featured in the commercial run by the 501(c)(3) Heroic Hearts Project and, to my knowledge, not in any other commercial, “C3 ad” may refer to the nonprofit television spot.

In an internal ballot committee report, the campaign notes “pre-interview for filming with Dr. Roxanne Sholevar” as an agenda item.

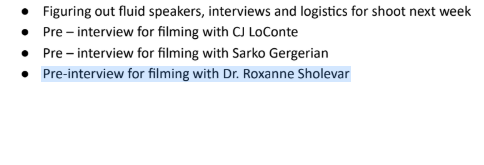

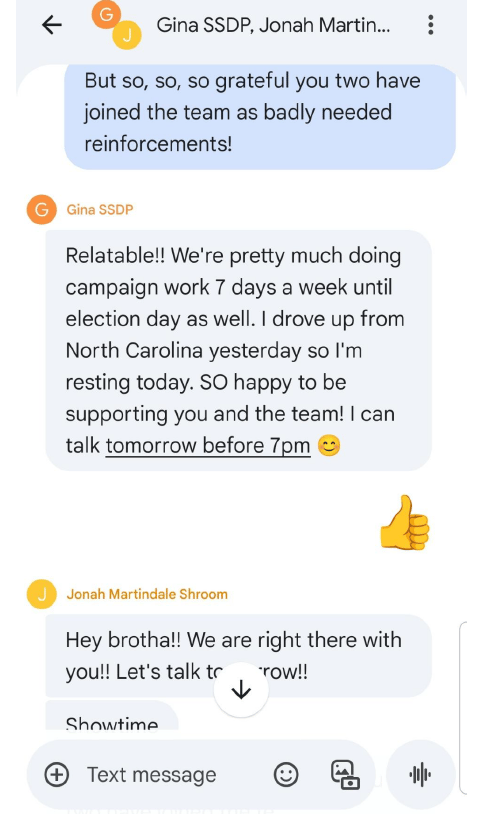

In internal ballot committee reports, the campaign noted having “confirmed Judi Fitts and Sarko Gergerian for ad campaign - JM” (the initials JM mean the confirmation was done by Jennifer Manley). Judi Fitts, featured in the Heroic Hearts Project advertisement, spoke in favor of Question 4 as a ballot committee-selected speaker at a campaign press conference in March 2024, was paid $2500 by the ballot committee for “Admin Services” per OCPF report, and was thanked by Manley in an August 1, 2024, email for “agreeing to be filmed to be in one of our videos/ads” (emphasis in italics mine). To my knowledge, the only commercial Fitts appeared in was that of Heroic Hearts Project.

Heroic Hearts Project’s advertisement and the ballot committee’s advertisements contained an identical tagline: “It’s regulated therapy, not for retail sale.”

A Heroic Hearts Project press release linked the nonprofit’s advertisement to Question 4.

The Heroic Hearts Project advertisement appears to have been produced by Hamburger Creative Group (“HGCREATIVE”), hired for “production” by the ballot committee.

The Heroic Hearts Project advertisement was screened at a private September 18, 2024, campaign fundraising event—attended by me and Jamie Morey—at which Moffat appeared to pitch prospective donors on contributing to keep the nonprofit’s commercial on air.

According to an eyewitness, Manley oversaw the shoot for the Heroic Hearts Project commercial, which was filmed the same day as an official campaign commercial.

To my knowledge, the second largest portion of Heroic Hearts Project’s potentially problematic expenditures was for Open Circle Alliance. As detailed extensively earlier in this postmortem, Open Circle Alliance coordinated closely with the ballot committee during the same period Heroic Hearts Project paid $56,000 each ($112,000 cumulatively) to Open Circle Alliance cofounders Stefanie Jones and Rebecca Slater for “Public Education Related to Natural Psychedelic Medicine”—from April through November 2024, the entire period during which the election and Open Circle Alliance coexisted. Notably, the Heroic Hearts Projects contracts Morey and I signed were also for “Public Education Related to Natural Psychedelic Medicine.” Heroic Hearts Project aside, I was implicitly told by the OCPF, in discussing a hypothetical, that Emily Oneschuk’s dual role with the ballot committee and the new nonprofit was legally risky because of the degree to which it complicated distinguishing the nonprofit’s interests from those of the campaign.

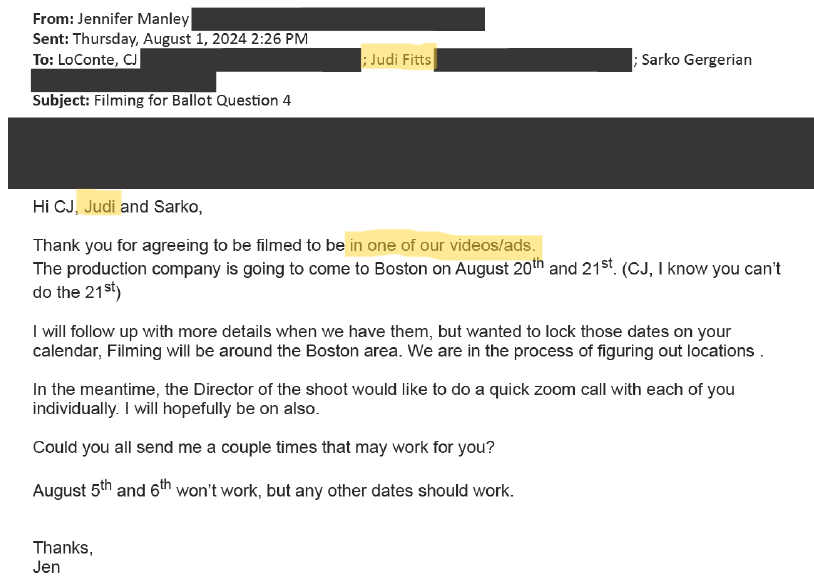

After those related to Open Circle Alliance, the next biggest Heroic Hearts Project expenditures relatively likely to draw OCPF scrutiny were those spent funding Students for Sensible Drug Policy (SSDP) organizers in Massachusetts, who were identified by SSDP as “SSDP’s Yes on 4 Campaign Educators” and functionally operated like campaign staff under my direction as educational outreach director, as demonstrated by our text messages.

That the SSDP organizers understood their roles to be campaign work is suggested by one of them in a group chat with me sharing: “We’re pretty much doing campaign work 7 days a week until election day as well” (emphasis in italics mine).

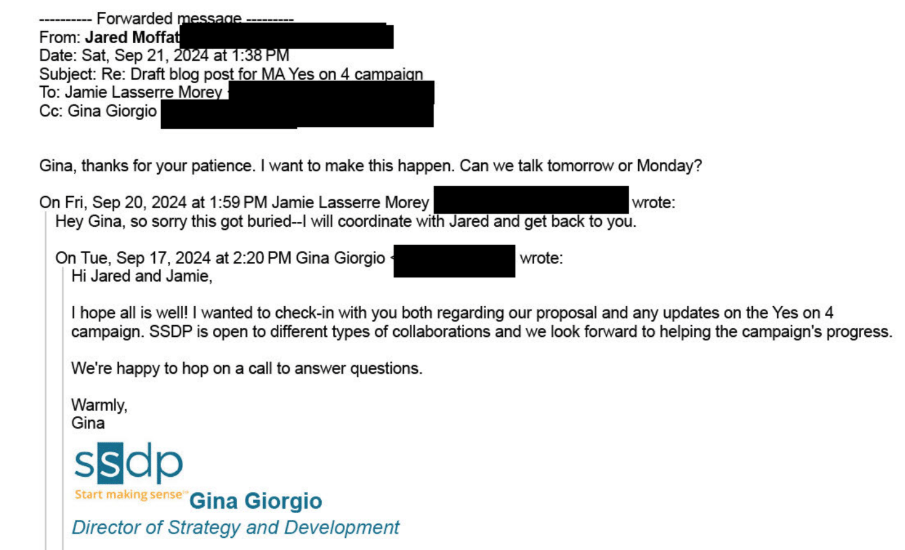

As reflected in internal emails, SSDP pitched a proposal directly to Yes on 4 campaign director Moffat to assist the campaign, with SSDP’s director of strategy and development even writing to Moffat that “we look forward to helping the campaign’s progress.”

But after Moffat signed off on an SSDP proposal, Heroic Hearts Project—rather than the ballot committee—paid the bill. Supported by this funding, SSDP organizers solicited endorsement signatures for the healthcare experts support letter and canvassed throughout the state with the support of the ballot committee’s strategic leadership. For a prime example, on election day, Moffat “asked [an SSDP organizer] to do an early morning shift in a Western Mass poll” as shown in the displayed text thread (emphasis in italics mine).

This closely coordinated activity, without clear organizational boundaries, put both SSDP and Heroic Hearts Project in a potentially precarious position with regards to state campaign finance law in the absence of reported in-kind contributions—and for no obvious benefit to campaign effectiveness—similar to the way Morey and I were bonused and Emily Oneschuk was diverted from core organizing to launching a new nonprofit. Regardless of whether the OCPF determines laws were broken, the dysfunction evident throughout the ballot committee’s operations suggests conservative adherence to regulations might have prevented organizational bloat and contributed to more coherent strategic leadership—in addition to protecting grassroots advocates, nonprofit partners, and movement credibility.