Why the Question 4 Campaign Fell Short, Part 6.2

A Multimillion-Dollar Shortfall, A Contradictory Spending Strategy and more

By Graham Moore

WHY THE CAMPAIGN FELL SHORT: 6.2

A Multimillion-Dollar Shortfall

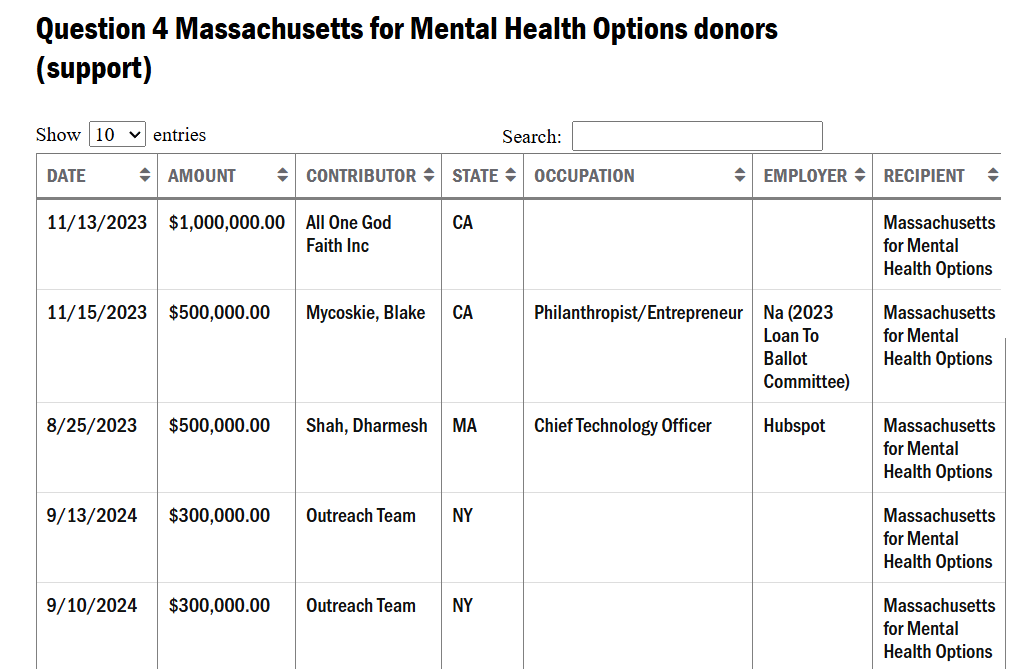

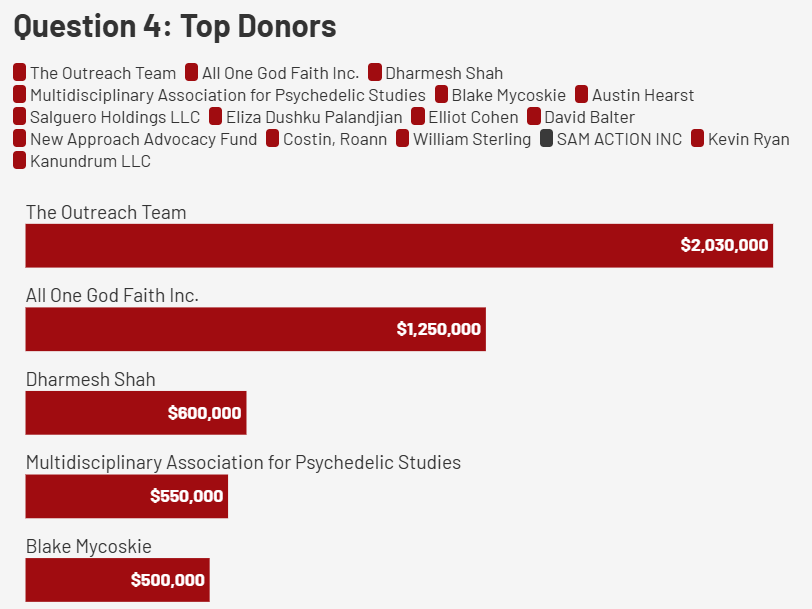

As noted earlier in this postmortem, Yes on 4’s strategic leadership claimed the campaign did not have the resources to win. While the campaign had a fundraising target of $10,000,000, the ballot committee raised only $6,670,956.01 in monetary contributions. Officially, these monetary contributions were complemented by just $186,654.32 of in-kind contributions—excluding the $285,070 in-kind contribution from The Outreach Team intended as a refund. This means the campaign officially had less than $7,000,000 to spend, far short of its goal.

In public reporting, the ballot committee’s fundraising was repeatedly grossly overstated by improperly counting The Outreach Team’s refunds as regular contributions rather than as non-contribution receipts—apparently with no requested corrections by the campaign. For example, an October 24, 2024, New England Public Media article stated, “The campaign aiming to legalize certain psychedelics in the state, through Question 4, has received about $7.4 million.” For another example, Boston.com’s October 2024 post-election coverage characterized “Outreach Team” as one of the ballot committee’s largest contributors, alongside David Bronner’s company and billionaire Dharmesh Shah:

On the eve of the election, Boston University News Service even incorrectly identified The Outreach Team as the largest donor to the Question 4 campaign:

The media coverage belied the shortcomings of Yes on 4’s fundraising. In fact—excluding refund contributions from The Outreach Team and a $60,000 four-month loan from New Approach Advocacy Fund—the ballot committee officially raised a paltry $41,851 over the first eight months of 2024. The campaign subsequently cancelled over $800,000 of previously reserved television advertising slots for fall 2024.

To my knowledge, no one took responsibility for the drop-off in contributions, and I was never told who was primarily in charge of fundraising. Yes on 4 strategist Lynda Tocci told me explicitly that it was not her job to solicit donations. Although I knew New Approach executive director Graham Boyd, campaign manager/ballot committee chair Danielle McCourt, and Yes on 4 campaign director Jared Moffat were involved in fundraising, as reflected in the communications displayed below, I did not learn to what degree they were individually responsible and who else, if anyone, was.

Similarly—other than being told after the fact that it was difficult to fundraise given the political circumstances—I was not provided an explanation for the shortfall. Nor was I informed the ballot committee was struggling to solicit contributions until August 2024; rather, I had been repeatedly assured the campaign was on track, despite the abrupt scaling back of Emily Oneschuk’s grassroots campaign director role amid other disruptions. While it was upsetting for me to later hear from a supportive bundler that certain members of Yes on 4’s strategic leadership repeatedly claimed to be too busy to coordinate fundraising with them during the campaign, it is possible these particular leaders were, like myself, under the false impression someone else was adequately handling it.

An Outreach Strategy at Odds With Polling

One of the contributors to a successful ballot question campaign that Yes on 4 strategist Lynda Tocci detailed in her 2024 podcast appearance was recruiting convincing “mini messengers” (complete, rough AI transcript here). She recalled how one previous campaign, related to rideshare policy, “talked to over 38,000 drivers” and another previous campaign, related to nurse staffing, “[activated]” “thousands of nurses” to convey its messaging. Elaborating on what makes an effective “mini messenger,” Tocci said:

[Voters] will look for information. If there’s a nurse staffing question, they’re going to ask a nurse. If there’s a question on charter schools, they’re going to talk to a teacher. And so I think as we got better, running fuller campaigns and engaging more people in the process, we had more mini messengers out there for people to talk to. So those [mini] endorsements are almost as important as the bigger endorsements.

From its earliest days, Yes on 4 framed its initiative as focused on, in the words of campaign director Jared Moffat in 2023, “[addressing] the mental health crisis, especially for veterans, health workers, and first responders.” This framing included officially naming the ballot committee Massachusetts for Mental Health Options (MMHO). And preliminary survey data supported this approach, showing the most convincing arguments for the ballot question were:

“Hospice providers and end-of-life medical practitioners support this question to allow natural psychedelic medicine therapy for terminally ill people” (78% found convincing);

“Pioneering research from leading medical research institutions [...] finds that natural psychedelic medicines can be effective in treating depression and anxiety” (77% found convincing);

“Veterans are facing a PTSD crisis. [...] This question allows people with PTSD who have already tried therapy and pills without success a chance to recover and truly heal” (76% found convincing).

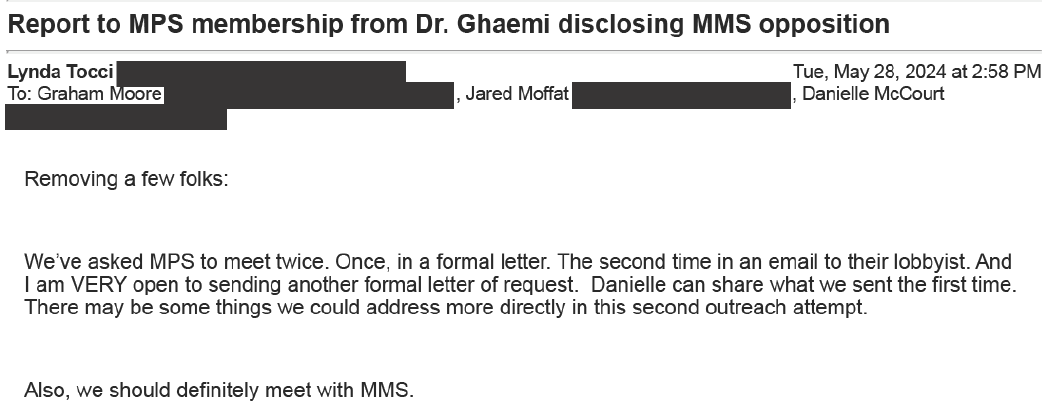

Accordingly, strategic leadership identified the campaign’s most valuable messengers as, in the words of Yes on 4’s pollster, “doctors, scientists, care providers, and veterans.” But—as alluded to in prior analysis of the ballot committee’s wooing of activist James Davis—the ballot committee neglected outreach to these messengers at key periods, particularly the formative, first eight months of the campaign. Illustrating the point, when I suggested greater engagement with medical professional organizations a few weeks after I was hired in May 2024, Tocci revealed in an email that the ballot committee had only asked to meet with the Massachusetts Psychiatric Society (MPS) twice so far. In the same email, she seemed to confirm the ballot committee had not even tried meeting the Massachusetts Medical Society (MMS).

For comparison, as described earlier in the postmortem, the ballot committee had already met with psychedelics decriminalization activist Davis—who was not a healthcare professional, scientist, veteran, or first responder—multiple times, sent him numerous outreach invitations, and donated $35,000 to his organization. And while Tocci agreed with me in her email that further communication with medical professional organizations could be worthwhile, this was more than a month after MPS and MMS had formally come out against the ballot question.

Even after the email exchange, the campaign did not make substantive headway in organizing healthcare professionals en masse until I pushed for a press conference and proposed—and began circulating—a sign-on endorsement letter for healthcare professionals in late September 2024.

Over the next five weeks through my initiative, the campaign recruited over 300 healthcare expert endorsers of Question 4, including over 50 MDs and over 20 current and former psychedelics researchers. The high value of these endorsements—as indicated by polling—was acknowledged by the campaign’s strategic leadership, who rapidly incorporated them into campaign messaging. For example—at my suggestion—our television advertising for the final two weeks of the election explicitly mentioned hundreds of healthcare expert endorsers.

The campaign also quickly marshaled an impressive speakers lineup for a healthcare professional supporters press conference, which was held a week before election day. Featured speakers included world-renowned psychiatrist and trauma expert Dr. Bessel van der Kolk as well as a psychiatrist director of the psychedelics research program at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). If survey data is any guide, Question 4 likely would have received substantially more support from voters had the ballot committee conducted this kind of organizing during its earliest months, rather than only during its final weeks.

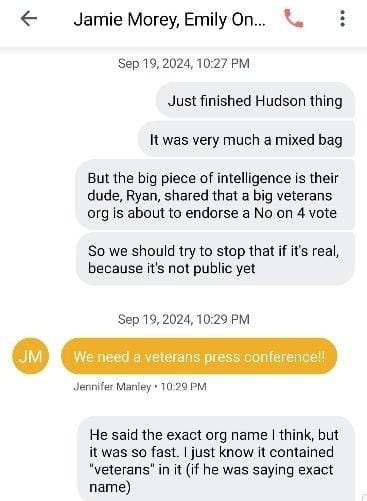

The rallying of veteran community support came similarly late. In stark contrast to the opposition to Question 4, which launched with the endorsement of the Massachusetts Psychiatric Society (MPS) and an MGH physician as its chair, it took Yes on 4 more than six months to begin deploying an official spokesperson who was not a professional political consultant. Furthermore, even though the campaign had—from its hiring of local veteran Emily Oneschuk as the nominal campaign director in 2023 onward—cloaked itself with a veteran identity, it only began garnering high profile endorsements from local veterans and veteran organizations in the last nine weeks, starting with the veteran executive director of the Bilingual Veterans Outreach Center of Massachusetts in Springfield on September 10, 2024. Strikingly, in response to me sharing nine days later in an internal group chat that I had heard the opposition acquired a veterans organization endorsement, the campaign’s de facto public relations director Jennifer Manley exclaimed over text, “We need a veterans press conference!!”—as if it was not her prerogative to organize one as appropriate (which it was).

The ballot committee did eventually hold a veterans press conference on October 10, at which Disabled American Veterans (DAV), Department of Massachusetts (DAV Massachusetts), representing over 60,000 disabled veterans in the commonwealth as the state chapter of Disabled American Veterans (DAV), endorsed Question 4. Demonstrating a gap in coordination, Yes on 4 campaign director Jared Moffat—who was out of state at the time—apparently learned of this endorsement from me texting him from the press conference and, recognizing its usefulness, promptly incorporated it into a “donor letter.”

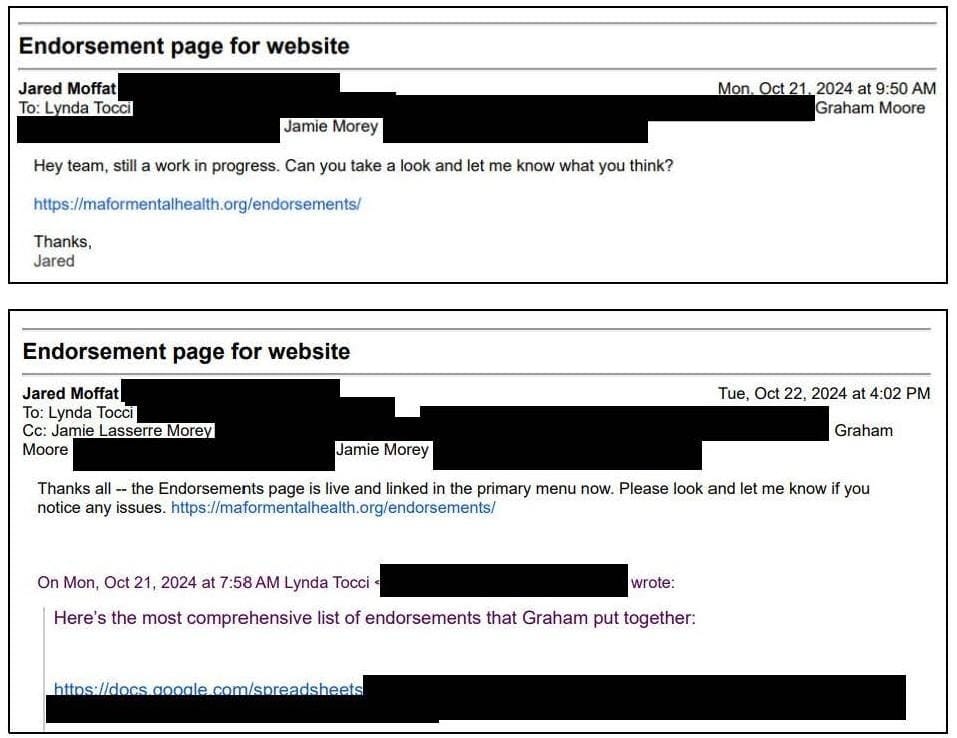

Unfortunately, the ballot committee was not as timely in sharing the endorsement with voters. As of the day of the press conference, Yes on 4’s website had never mentioned any endorsements because, according to Moffat in a text, he had not “had time” to add them to the website amidst “working 14 hour days”—a surprise to me who replied: “Had no idea you were the sole website guy.”

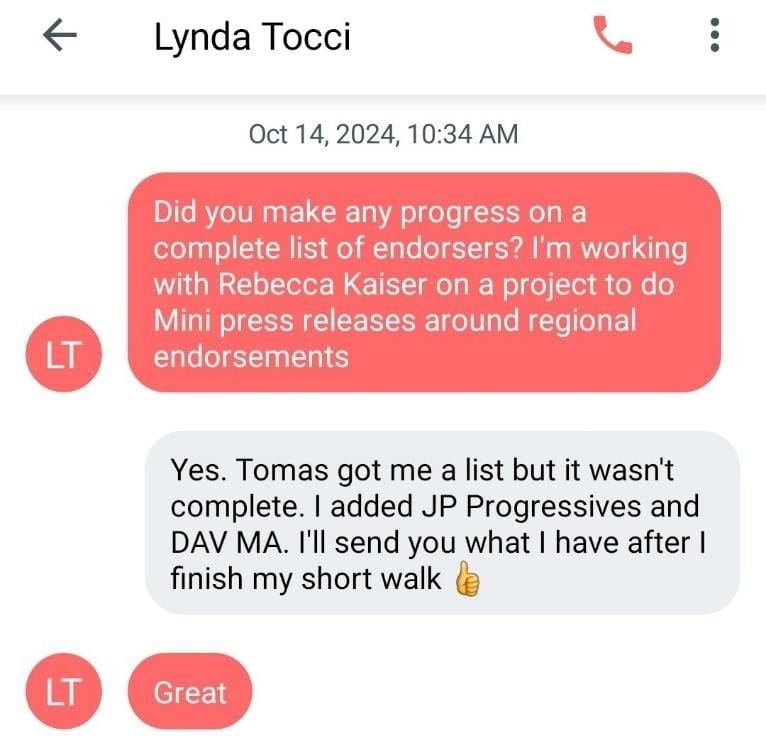

Moreover, the ballot committee did not even possess “a complete list of endorsers” as of mid-October 2024—so I put one together to facilitate adding them to the website, as reflected in the text conversation with Tocci displayed below.

The endorsements would not be featured on the website until October 22, after early voting had already begun and exactly two weeks before election day.

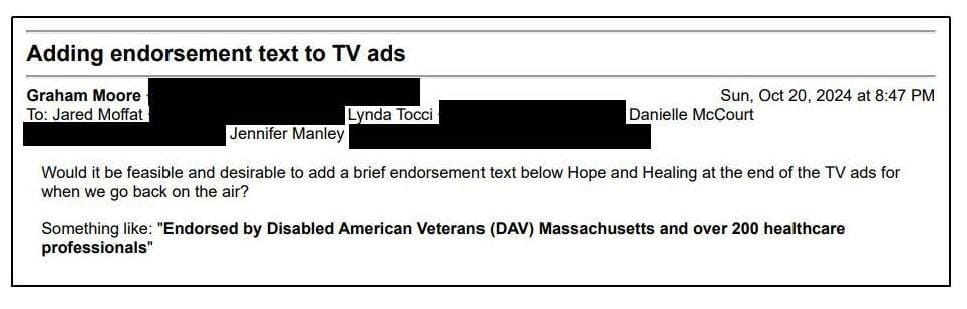

As in the case of the healthcare expert endorsers, strategic leadership affirmed the high value of the DAV Massachusetts endorsement by emphasizing it in our messaging, including by adding it to our television advertising at my suggestion.

If the support of DAV Massachusetts and hundreds of healthcare experts was worth the heavy promotion it received through Yes on 4’s talking points, website, and television advertising two weeks before election day, then it was worth galvanizing long before fall 2024—especially in light of the polling showing “doctors, scientists, care providers, and veterans” were the campaign’s most effective messengers. But, as with the other operational shortcomings previously detailed, no one in strategic leadership took responsibility for the lagging endorsements or for not replacing Oneschuk when she stepped back—a decision that deprived the campaign of a full-time organizer to activate the veteran community it claimed to represent.

A Contradictory Spending Strategy

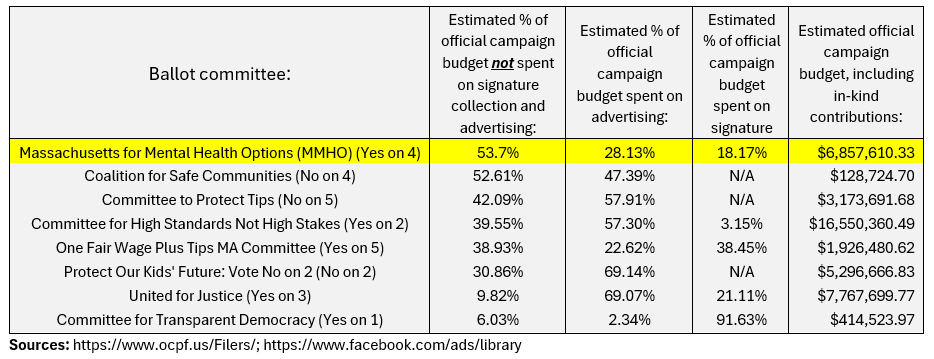

According to leadership of the Massachusetts ACLU, New Approach claimed Yes on 4 planned to concentrate campaign spending heavily on advertising—largely foregoing a field operation—as early as 2023. I, however, only became aware that the ballot committee did not intend to have a substantive field operation in summer 2024. I had previously volunteered extensively as a canvasser for the successful Freedom for All Massachusetts ballot question campaign (Yes on 3) in 2018, which had a big field operation despite a smaller budget than the 2024 psychedelics campaign. Consequently, I had been anticipating the deployment of mass door knockers and dialers across the state when I was informed by strategic leadership that available resources were to be concentrated on advertising, which was more cost effective than canvassing. I was told by a member of strategic leadership that an extensive field operation for our issue might even do more harm than good because the unique eccentricity of pro-psychedelics volunteers might turn off voters while going door to door. The latter argument was not convincing, but it was reasonable to prioritize getting on air over a ground game. The actual spending of Yes on 4, however, did not favor advertising, as illustrated by the data in the table below:

While every other contemporaneous ballot question campaign in Massachusetts—save the shoestring, less than $130,000 No on 4 campaign—allocated most of their official budgets to advertising and/or signature gathering, Yes on 4 did not. In fact, the Question 4 campaign spent less on advertising as a percentage of its official budget than all but two of the seven other ballot question campaigns—and the two laggards’ official budgets were less than a third of Yes on 4’s. Furthermore, that Yes on 4 only allocated 28.13 percent of its official budget to advertising—compared to 47.39 percent, 57.3 percent, 57.91 percent, 69.07 percent, and 69.14 percent among the campaigns that allocated more—could not be explained by overpaying for signature gathering. After factoring in refunds, the Question 4 campaign actually spent less on signature gathering as a percentage of its official budget, 18.17 percent, than all but one of the other Yes campaigns.

The money saved by these relatively modest outlays on key functions was not put into a field operation. While Yes on 3, which spent over 69 percent of its reported budget on advertising, claimed to have still built an extensive ground game, contacting “more than 160,000 voters directly, knocking on doors and calling” as described in a union press release, Yes on 4 never built the infrastructure to recruit and mobilize volunteers en masse, did almost no door knocking, and employed a tiny handful of junior Dewey Square Group staff in a part-time capacity to canvass a few thousand voters by phone.

What much of the money was put into was a grab bag of expensive professional services and part-time actual and nominal strategic leadership, including but not limited to:

$637,500.70 to Dewey Square Group, whose principals Lynda Tocci and Jennifer Manley co-led the campaign part time—this includes the $150,000 for lobbying to counter the organization the ballot committee paid $35,000 to;

$493,821.69—more than a quarter of the ballot committee’s $1,928,817.68 estimated advertising budget—in “video production” and “production” services;

$173,887.50 of “staff time” from New Approach Advocacy Fund, the employer of part-time Yes on 4 campaign director Jared Moffat, as in-kind contributions;

$161,000 to DLM Strategies, the personal consultancy of part-time campaign manager and chair Danielle McCourt;

$71,150 in “website services,” “website design services,” and “website design and log services,” which apparently did not preclude requiring the campaign director to manually update the website amidst “working 14 hour days.”

The $71,150 website that Moffat purportedly struggled to keep up to date was emblematic of a trend of premium prices not translating into premium performance for Yes on 4.

An Indifference to Outcomes

As alluded to throughout this postmortem, the campaign had a consistent slapdash style. Even though Jared Moffat and Danielle McCourt both oversaw the ballot committee in 2023, when it donated $35,000 to the organization of a divisive activist, subsequently failed to prevent that activist from effectively agitating against the campaign in the press and grassroots, and overpaid upfront by $2,000,000 for signature collection because of a printing error, they were both promoted to greater positions of leadership in the new year: McCourt to campaign manager and Moffat to campaign director. In Moffat’s case—according to Moffat as reflected in the text message displayed below—he had personally recommended the ballot committee make the ill-fated donation, and yet he was still entrusted to shepherd the launch of the new Massachusetts nonprofit Open Circle Alliance.

By the time Jamie Morey and I were hired by the ballot committee in May 2024, a culture of impunity among strategic leadership appeared entrenched and undermining organizational effectiveness.

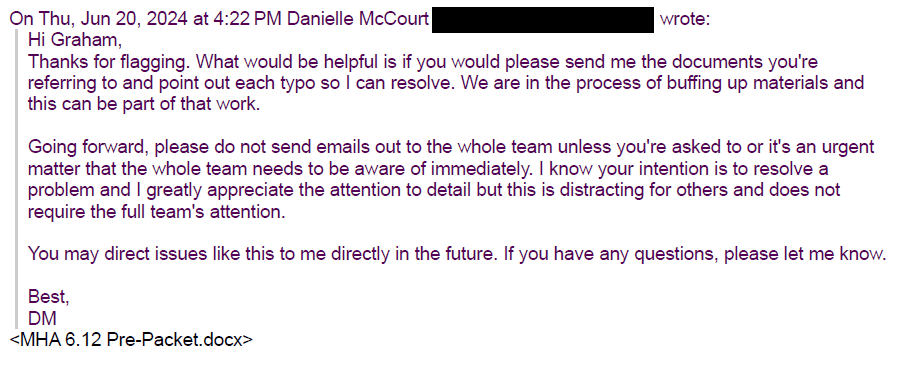

An early and illustrative case was my flagging an alarming prevalence of typos in outgoing communications in June 2024. Substantial typos were present in a pre-packet for the Clinical Issues Advisory Council of the Massachusetts Hospital Association (MHA) as well as in standard campaign literature used for canvassing. The errors in the pre-packet were especially troubling because Dewey Square Group’s then senior vice president of communications & strategy—and Yes on 4’s de facto communications director—Jennifer Manley had her name on it, and she should have reviewed it. A snapshot of the pre-packet with typos highlighted, including the misspelling of “association,” is displayed below.

In her reaction to me bringing this to the team’s attention in an intentionally non-accusatory and non-directive email, campaign manager McCourt did not accept responsibility or acknowledge the failure to detect and prevent widespread typos in campaign literature suggested a systemic issue. Rather, she replied in a new thread and placed the burden on me to resolve the typos on a case by case basis, which would not address the problem moving forward in the absence of improved quality control.

In a follow-up conversation on the phone, primary blame for the typo-ridden pre-packet was assigned to a junior Dewey Square Group staffer. The fact that Manley was also culpable as our public relations strategist—as well as the only campaign official with her name on the document—was glossed over. And Manley did not participate in the call.

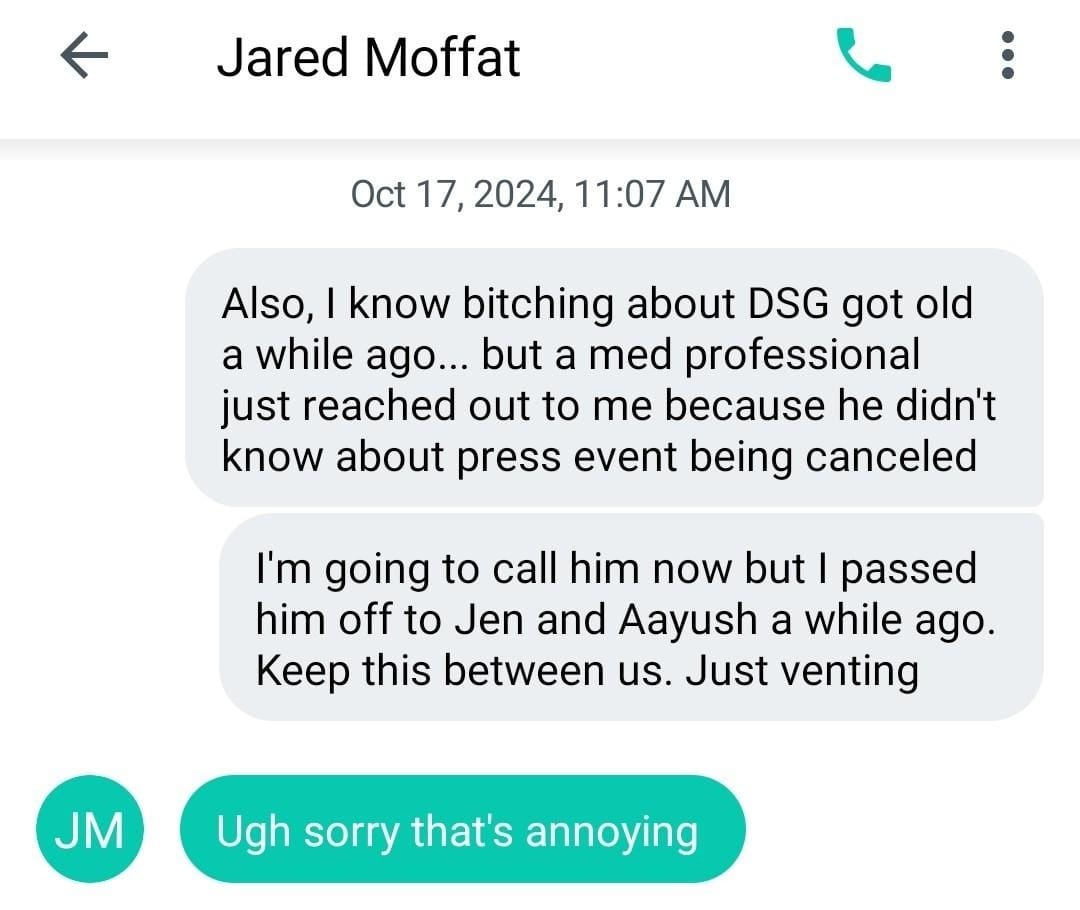

Demonstrating the persistence of this leadership culture, one of Question 4’s healthcare expert endorsers—who the ballot committee had recruited as a potential press conference speaker—found himself literally left out in the cold by the campaign less than three weeks before election day. The individual had taken time off from work to attend Yes on 4’s healthcare professional supporters press conference but, when they arrived in downtown Boston one chilly morning, no one was there—the ballot committee had rescheduled the event without letting them know. It was Manley’s responsibility to vet and coordinate speakers, and I had passed the healthcare expert off to her assistant days ago in accordance with her direction. To my knowledge, however, she did not take responsibility for the incident, and someone convinced the healthcare expert that the campaign was largely run by volunteers, a falsehood that seemed to conveniently mitigate his frustration. Even if there had been an appetite for enforcing accountability, there was too little time before voting concluded for it to be practical. Moffat at least acknowledged the mishap as “annoying” when I texted him to vent.

These expressions of indifference regarding the quality of performance were not isolated incidents but symptoms of the campaign’s core flaw: a leadership structure that discouraged accountability while conflicts of interest went unaddressed.