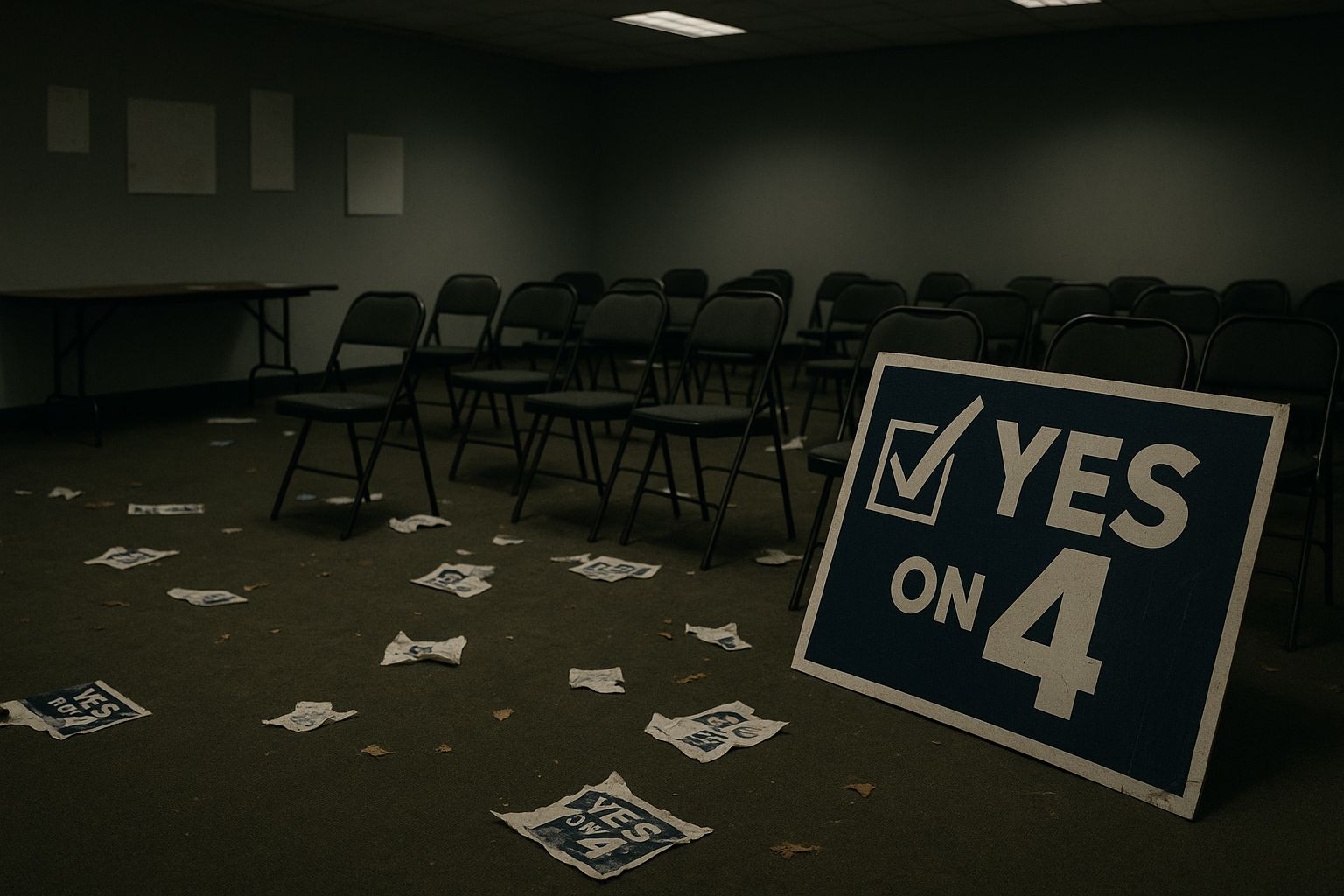

Why the Question 4 Campaign Fell Short, Part 6.1

The Campaign Avoided Accountability as Shortcomings Mounted Amid Unaddressed Conflicts of Interest

By Graham Moore

6.1 - The Campaign Avoided Accountability as Strategic and Tactical Shortcomings Mounted Amid Conflicts of Interest

A Through Line

As referenced in the preceding sections, the campaign experienced serious deficiencies from the outset. Apart from possibly illegal activity, the remaining issues through election day that were not previously detailed—too succinctly characterized and numerous for lengthy individual sections—are examined here. The through line is the avoidance of accountability as shortcomings stacked up, amid unaddressed conflicts of interest.

A Strained Scope of Loyalty

As originally characterized to Jamie Morey and me by Yes on 4 campaign director Jared Moffat and Yes on 4 chief spokesperson Emily Oneschuk, the campaign was intended to have a collaborative and distributed leadership model: local veteran Oneschuk—directly supervising, and supported by, Morey and me—leading the campaign as “grassroots campaign director” in collaboration with New Approach, two Dewey Square Group principals, and the campaign manager and ballot committee chair, Danielle McCourt, with her own boutique consultancy called DLM Strategies. To my knowledge, the only staffer officially hired to work on the campaign full time was Oneschuk but—for the vast majority of the campaign—no one, including Oneschuk, was actually working on the campaign full time. Relatedly, for the vast majority of the campaign, all ballot committee staff—save for me—had other paid roles, including Oneschuk at a dive shop. This meant practically everyone working for Yes on 4 had competing professional responsibilities diverting focus from the ballot initiative, with varying levels of conflict of interest.

A few of the clearest conflicts of interest arose from corporate lobbying clients of Dewey Square Group. At the same time as being the campaign’s de facto communications director, Dewey Square Group’s Jennifer Manley was lobbying the Executive Office of Health and Human Services (EOHHS)—where influential Compass Pathways board member Linda McGoldrick was on the Health Information Technology Commission—on behalf of Bamboo Health, a mental healthcare information technology company. Per McGoldrick’s LinkedIn, she was “a recognized international leader in life sciences, healthcare, mental health, behavioral health, and global health systems,” serving on multiple high profile New England boards, including the board of Lahey Hospital & Medical Center. Furthermore, McGoldrick had long served as a “senior advisor” for a specialist Massachusetts consulting firm, whose clients overlapped with those of Dewey Square Group—particularly multiple members of the Massachusetts Hospital Association, the primary funder behind a 2018 ballot initiative campaign that paid Dewey Square Group over $1.1 million, and Tenet Healthcare (Tenet Health), one of Dewey Square Group’s largest Massachusetts state lobbying clients for over a decade.

Compass Pathways was a for-profit corporation conducting clinical research in Massachusetts to develop psilocybin as a pharmaceutical medication, which meant it stood to lose money if Question 4 became law—especially if that led to ongoing momentum for state by state decriminalization of psilocybin. Compass Pathways had not been timid in opposing non-pharmaceutical competitors. As highlighted by David Bronner, one of Question 4’s biggest proponents, Compass Pathways had even tried to sabotage Oregon’s regulated access program for psilocybin in 2021. And, in 2024, Compass Pathways employed a registered lobbyist in Massachusetts on March 27—the day immediately following Question 4’s legislative hearing—to lobby the Department of Veterans Services within EOHHS as well as the governor’s office regarding “legislation and regulation regarding psilocybin.” Especially given Compass Pathways’ in-state activity, if Manley’s public relations strategy for the ballot initiative upset the company—such as by undermining Compass Pathways’ contemporaneous talking points about the importance of heavily regulating psilocybin—it might have compromised Manley’s ability to lobby EOHHS effectively on behalf of Dewey Square Group’s corporate client Bamboo Health.

Even apart from the presence of Compass Pathways, Manley’s corporate lobbying for Bamboo Health and another corporate client, Molina Healthcare—simultaneous with her co-leading the Question 4 campaign—posed conflicts of interest. And, in the case of Molina Healthcare, Manley took over the account from another Dewey Square Group lobbyist months after Manley had started working for the campaign. Both Bamboo Health and Molina Healthcare earned substantial revenue related to the provision of conventional behavioral health treatments. Consequently, a reduction in demand for substance use recovery and psychiatric care, or a diversion of behavioral health spending to outside the mainstream healthcare system—both of which were outcomes proponents of Question 4 hoped the measure to eventually accomplish—were threats to the companies’ bottom lines. And Molina Healthcare specifically had been repeatedly investigated for aggressively and illegally exploiting patients for profit. As recently as 2022, the office of then state attorney general Maura Healey alleged a local subsidiary of Molina Healthcare was responsible for “fraudulent claims [being] submitted to the state’s Medicaid Program, known as MassHealth, for behavioral health care services,” forcing the company to pay a $4.6 million settlement. If Manley’s Yes on 4 messaging suggested lightly regulated access to psychedelic therapy outside the conventional healthcare system could dramatically reduce behavioral healthcare costs, it could undercut arguments in support of her corporate lobbying clients. I first learned of these conflicts of interest in 2025, after I was no longer employed by the ballot committee—to my knowledge, no actions were taken to mitigate them.

Other conflicts of interest stemmed from the new Massachusetts nonprofit Open Circle Alliance, dedicated to—in the words of Oneschuk at a launch event—“developing the psychedelic community within MA, educating on psychedelic substances and opening conversations about an array of different psychedelic policies.” As previously mentioned, Oneschuk was officially Open Circle Alliance’s treasurer and resident agent from April 19, 2024, to July 24, 2025, overlapping with her employment by the ballot committee for more than eight months (Oneschuk’s contract with the ballot committee went through December 2024). Moreover, Oneschuk served as a spokesperson for the nonprofit for two months, headlining two launch events. As a founding director and launch speaker, Oneschuk was structurally empowered to play a prominent role in directing Open Circle Alliance’s operations. And, as treasurer and resident agent, Oneschuk was officially responsible for fielding legal correspondence on behalf of the nonprofit as well as managing the nonprofit’s finances. But while Open Circle Alliance was purportedly independent from the campaign, Oneschuk’s primary employer was the psychedelics ballot committee—which had a vested interest in “developing the psychedelic community within MA, educating on psychedelic substances and opening conversations about an array of different psychedelic policies.” If Oneschuk led Open Circle Alliance in a direction opposed by the campaign’s strategic leadership, it might have jeopardized her lucrative position with the ballot committee.

While Open Circle Alliance’s other founders, Stefanie Jones and Rebecca Slater, claimed their treasurer’s conflict of interest was mitigated by Oneschuk “[stepping] back” from the nonprofit in June 2024, this was not publicly announced contemporaneously. Furthermore, Oneschuk continued to represent Open Circle Alliance on its official website—with no mention of a step back—for another year, and she only officially resigned as treasurer in July 2025. To my knowledge, firm boundaries demarcating Oneschuk’s work for Open Circle Alliance from her work for the campaign were not drawn—nor were the nonprofit’s origins as a collaboration with ballot committee organizer New Approach made publicly transparent—contributing to a diversion of resources that adversely affected the campaign, as detailed in Part 3.

Another conflict of interest related to Open Circle Alliance had to do with Jones’ personal relationship with Moffat, who she characterized during a recorded panel in December 2024 as a “longtime friend[] and colleague[]” that she had known from “his earliest days” in drug policy reform over a decade ago (complete, rough AI transcript here). She also stated Moffat had recruited her to participate in the Massachusetts psychedelics campaign and—after a conversation with Moffat led to the idea for Open Circle Alliance—Moffat had “put [her] in touch with” her nonprofit cofounders, including Moffat’s de facto employee Oneschuk. Presumably Moffat, as then deputy policy director of New Approach, had also played a substantial role in the funding for Open Circle Alliance that Jones and Slater later acknowledged had “originated in collaboration with New Approach.”

When Moffat pitched Open Circle Alliance to me in February and March 2024, he told me the nonprofit was his brainchild, barely mentioned Jones, and did not give any indication Jones—or his longstanding friendship with her—had played any role in generating the proposal for a new donor-funded organization. Rather, I was led to believe that Jones, who had never founded her own corporation before, had been vetted and selected as an independent candidate for the new nonprofit directorship. Only while watching the aforementioned December 2024 panel did I hear that Open Circle Alliance had—from its beginning—been intended to be founded by Jones, Moffat’s “longtime friend.” I remain unaware of any action taken to mitigate potential bias on the part of Moffat toward Jones that might have influenced him to advance her career at the expense of the campaign (even unintentionally).

As the deputy policy director of New Approach, a leading fundraiser in the drug policy space, as well as a strategic leader of Yes on 4, Moffat was uniquely positioned to obtain funding for a new drug policy organization and then promote it through the ballot committee, which he did for Open Circle Alliance. While he might have genuinely believed Jones’ skillset, the new nonprofit, and the ballot committee would be synergistic, Open Circle Alliance ultimately accomplished very little at relatively a steep cost.

A 2025 email from Slater further suggested a lack of transparency exacerbating conflicts of interest. In response to former Yes on 4 community outreach director Jamie Morey raising concern over conflicting explanations for Open Circle Alliance’s origin—Slater had recently told community members in a virtual meeting that Open Circle Alliance had been seeded by the veterans nonprofit Heroic Hearts Project, independent of New Approach—Slater replied: “Jared [Moffat] told me a lot of things...being completely new to the legislative process, it took me a while to realize I frequently only got part of the story and he was doing what he was paid to do.”

Six days later, Slater and Jones emailed a joint statement admitting “the idea and funding for [Open Circle Alliance] originated in collaboration with New Approach” while declaring they would “not be responding to or further engaging with these insulting claims”—referring to what they called “accusations about rate of pay and efficacy.” Consequently, to what extent Slater “only got part of the story,” and what she meant by remarking Moffat “was doing what he was paid to do,” are still unknown to me. Regardless, Open Circle Alliance’s ties to New Approach—a major organizer of the ballot committee—should have been clearly disclosed to the public as a potential conflict of interest as the nonprofit claimed to be “not associated with the Yes on 4 campaign” and to “strive[] to present clear and neutral information.”

Similarly, Heroic Hearts Project—which endorsed Question 4 but reported no monetary or in-kind contributions to the campaign—should have clearly disclosed to the public its funding to support Open Circle Alliance, a nonprofit officially cofounded by campaign staffer Oneschuk, as a potential conflict of interest.

In addition to the specific acute conflict of interest issues detailed above, the campaign’s staffing structure generally increased the likelihood of potential and actual conflicts of interest compromising the effectiveness of Yes on 4’s strategic leadership. It is typical for experienced political consultants—such as McCourt and the campaign’s Dewey Square Group strategists—to work with a diverse range of clients, often simultaneously. For these specialists, balancing numerous, sometimes conflicting, professional loyalties over time is par for the course. And their professional success depends on not sacrificing valuable long term relationships for short term gain. While this does not necessarily mean they will intentionally make decisions to advance their careers at the expense of a project, it biases their decision-making in a way that can adversely affect their performance from a client standpoint—particularly when the optimal strategy for a client risks harm to the consultant brand. Clients willingly accept this possible downside in order to leverage the consultants’ expertise. The more a client can align their long term interests with that of their political strategists, the less the jeopardy.

In the case of Yes on 4, the absence of any single individual or entity being clearly responsible for the success of the campaign, combined with a more or less entirely part-time staff, increased the hazard from conflicting loyalties. The only campaign official identified as the leader to the public at large—as well as the only staffer officially hired to work on the campaign full time—was Oneschuk as “grassroots campaign director,” and she, as detailed in Part 4, was not even a full-time organizer, let alone a strategic or operational leader, for much of the campaign. Oneschuk took down her LinkedIn shortly after the election and, to my knowledge, has since avoided characterizing her role for the campaign as a leadership role. For example, in a November 2025 “alum” profile of Oneschuk by a nonprofit, the two paragraphs referencing her work for the ballot committee claim she was “approached to advocate for [(not lead)] a 2024 ballot question” and do not include her title or suggest she had more than a spokesperson role.

For another example, as early as March 2025, Oneschuk—who had already taken down her LinkedIn profile—was spotlighted in a LinkedIn post by the psychedelics-focused Lucid Institute that did not mention her involvement in Yes on 4 or electoral politics whatsoever, even though Oneschuk had been employed by the ballot committee only a few short months ago.

Moffat, too, avoided characterizing himself as a campaign director after the election. Although Moffat, who worked for Yes on 4 part time and almost entirely remotely from out of state, identified himself as “Yes on 4 campaign director” in select communications in the election’s final months, his official title was never publicized by the ballot committee. And Moffat was not described as Yes on 4’s campaign director in either his “Lessons from the Massachusetts Ballot Campaign” panel for the Chacruna Institute in December 2024 or in his “What Could the Next Iteration of a Psychedelic State Policy Look Like?” panel for Psychedelic Science in June 2025. Moreover, in providing comment for the Boston Globe regarding allegations of campaign finance violations by Yes on 4 in 2025, Moffat was quoted simply as “former policy director for New Approach Advocacy Fund.” As of writing on December 16, 2025, Moffat characterized his involvement with Yes on 4 on his LinkedIn profile as: “Led successful ballot qualification and advised 2024 Massachusetts ballot campaign for access to natural psychedelic medicines.”

The campaign’s Dewey Square Group strategists and ballot committee chair have been similarly cryptic. Although her boutique consultancy, DLM Strategies, was compensated $161,000 by the Yes on 4 ballot committee exclusively for “strategic management,” and she served as Yes on 4’s part-time campaign manager as well as its part-time ballot committee chair, McCourt has never publicly identified herself as Yes on 4’s campaign manager, and her LinkedIn profile, as of writing, does not mention the ballot measure campaign—but prominently mentions her finance director roles for two other statewide campaigns, including one that lost by a larger margin than did Question 4 and for which she was compensated just $17,902.19, primarily for “payroll.”

McCourt, identified only as “chairperson of the ballot question committee,” declined to provide comment for the aforementioned Boston Globe reporting, and, to my knowledge, did not provided comment for any news coverage of the Massachusetts psychedelics campaign, obscuring her leadership role. Illustrating the point, a donor who contributed more than $300,000 to the ballot committee claimed they were unaware of who McCourt was when McCourt came up in a private discussion about Yes on 4 with a friend of mine in 2025.

Together, the Dewey Square Group principals employed part time by the ballot committee were more publicly associated with the campaign than McCourt, but they also avoided publicly clarifying their leadership roles for Yes on 4—even though Dewey Square Group was compensated $637,500.70 by the ballot committee almost exclusively for “strategic consulting.” Manley was frequently quoted by media outlets as “a spokesperson” for the ballot committee, but only drug policy beat reporter Jack Gorsline—who was practically embedded with the campaign for months—reported Manley “played an integral role in shaping the Yes on 4 campaign’s messaging and steering its public relations strategy,” and he only did so for a single October 2024 article. To my knowledge, Yes on 4’s part-time chief strategist Lynda Tocci (the “head honcho of the overall campaign” according to Oneschuk) has never been reported as being as a major strategic leader of the ballot committee, and she has only spoken on-the-record about consulting for the campaign on two occasions: for a September 2024 podcast and for the just referenced October 2024 article by Gorsline. In neither case did Tocci identify herself as a primary leader of Yes on 4. Gorsline is the only journalist to have assigned foremost responsibility for the failure of the psychedelics ballot question to Dewey Square Group’s leadership, which he did in a December 2024 op-ed without mentioning Manley or Tocci by name. The part-time Dewey Square Group strategic leaders had a close working relationship with the part-time campaign manager, as reflected by McCourt using an @deweysquare.com email during the campaign.

While McCourt internally referred to New Approach executive director Graham Boyd as “the client” of the ballot committee, I do not know to what extent he was actively involved with strategy or operations. As a leader, Boyd stayed out of the spotlight as well. The single published media interview explicitly touching on the campaign that he participated in left his precise role for Yes on 4 ambiguous. Furthermore, the interview’s focus was the broad sweep of Boyd’s work in drug policy reform, with much more attention given to Boyd’s vision for New Approach nationwide beyond the Massachusetts campaign than on the Massachusetts campaign itself. To Morey and me, Boyd appeared to have a mostly hands-off approach to the ballot committee, and I had minimal, albeit entirely positive, personal interactions with him, during which he complimented my performance as a writer and public speaker. The practical authority of Moffat, McCourt, Manley, and Tocci, however, was very tangible.

With all of Yes on 4’s strategic leaders being part-time and having other high-stakes professional roles—such as “[overseeing] nationally coordinated ballot measure and state legislative strategy” per Moffat’s LinkedIn—and none of them being clearly individually responsible for strategic outcomes, they were disincentivized from prioritizing the campaign over projects for which they were more directly professionally accountable. Manley’s case was a prime example. Manley was just “a spokesperson” (emphasis in italics mine) for the ballot committee publicly, and, behind-the-scenes, she was one of at least four active strategic leaders for Yes on 4, including Tocci, McCourt, and Moffat. By contrast, Manley was the registered Massachusetts state lobbyist for both Bamboo Health and Molina Healthcare, the latter of which was one of Dewey Square Group’s most valued clients as reflected by Molina Healthcare being spotlighted as a client—in addition to Microsoft, Tenet Healthcare, and the UFC, among other corporate big names—on the Dewey Square Group website.

As the owner of the Bamboo Health and Molina Healthcare lobbying accounts for Dewey Square Group in Massachusetts (DSG Boston), she was directly and unambiguously responsible for delivering for them as clients, key to maintaining their business far beyond the end of the ballot question campaign. If Yes on 4 fell short, the blame would be distributed among her colleagues and numerous other factors; if Yes on 4 succeeded, the credit would likewise be diluted. All other things being equal, Manley’s lobbyist work had both greater potential upside, and greater liability, then her work for the ballot committee. If conflict of interest forced her to prioritize one professional obligation over the other, her optimal individual choice in isolation was likely to be preferencing her lobbying at the expense of the campaign. Other leaders were in similar positions.

Accordingly, Yes on 4’s strategic leadership was structurally discouraged from enforcing accountability within the campaign, because doing so would require assuming greater individual responsibility for outcomes, and thus greater professional risk, than their peers. In such an environment, any given strategic leader was more vulnerable to actual and potential conflicts of interest compromising their effectiveness than they would have been had they worked for the ballot committee full time or knew they would be held directly responsible for a loss.

Moreover, with little transparency into strategic leaders’ other projects and the nature of their work, it is plausible that actual and potential conflicts of interest were substantially greater than indicated by the information already laid out. While limited details of certain professional activities—like lobbying—are legally mandated to become public, most details of most professional activities—including political consulting—are not. For example, while I am not aware of any evidence that Compass Pathways has ever been a client of Dewey Square Group, if Compass Pathways was a Dewey Square Group client—even if it was employing a consultant working for Yes on 4—that information could legally be kept secret depending on the nature of the work. Compared to Compass Pathways’ over $630 million market cap, the considerably less than $10 million officially spent on the campaign was peanuts. And, as previously alluded to, Compass Pathways was only one of numerous corporations with financial incentive to oppose legislation like Question 4.

I have not accused, and am not accusing, any individual or entity of willfully, secretly sabotaging Yes on 4 from the inside. My intention is to make clear the degree to which the campaign was potentially jeopardized by its organizational structure. I do not know of any safeguards put in place to mitigate potential conflicts of interest, and covert, intentional self-sabotage, while unlikely, remains a plausibility.

From a theoretical standpoint, there are advantages to defeating a campaign like Yes on 4 through covert, intentional self-sabotage rather than through a formal opposition campaign. One of the biggest benefits is deniability. Campaign finance and lobbying laws mandating baseline transparency, and mainstream political reporting for which following the money trail of campaigns and lobbyists is standard fare, make it more difficult to conceal support for overt opposition than to conceal support for covert opposition. Another benefit is the uniquely damaging cascade effects of a loss that is perceived to be self-inflicted rather than delivered by a competent or overwhelming foe. If the electoral defeat is inaccurately attributed primarily to the policy itself, rather than to organized opposition or managerial incompetence, the policy is less likely to be replicated by proponents elsewhere, even with more favorable conditions.

Among the notable disadvantages of covertly causing a campaign like Yes on 4 to self-sabotage are the potentially severe legal and reputational consequences of getting caught. This vulnerability can incentivize various degrees of blackmail among conspirators and force even acrimonious partners to remain affiliated indefinitely to preserve the secret. A high level of deniability is typically not worth the risk and opportunity cost of employing certain kinds of political black ops.

Within the healthcare industry, though—given certain assumptions—there are clear incentives to secretly oppose expansive access to psychedelics. As touched on earlier, corporations that either profit from, or stand to profit from, treating behavioral health conditions are financially incentivized to oppose legislation that would divert business from them or reduce demand for their goods and services. If such corporations judged that liberal psychedelics policies—like allowing individuals to freely grow and share psilocybin mushrooms—posed a relatively high risk of substantially reducing mental illness and addiction without generating revenues, then shareholder primacy would dictate many of them combat liberal psychedelics policies.

However, it would not be politically or culturally feasible for these corporations to openly oppose people getting healthier. And, to the extent psychedelic therapies are effective, market forces would encourage these same corporations to try to monetize psychedelics ahead of competitors, making demonizing psychedelics in general counterproductive. The challenge they would face is how to prevent psychedelics from being made available in a way that does not benefit them financially, without excessively compromising their capability to use psychedelics to generate revenues. A possible solution would be to secretly engineer an electoral defeat that politically and culturally discredited making psychedelics available outside their purview. This would allow them to have their cake and eat it, too: continue hyping the urgency of delivering effective treatments to patients as a marketing tactic, while simultaneously throttling accelerated access for the benefit of shareholders at patients’ expense.

While the 2024 loss of a psychedelics ballot measure in Massachusetts was most likely not the result of intentional self-sabotage, certain interest groups appear to have seized on the outcome to discourage access to psychedelics outside the mainstream healthcare system nationwide. A prominent example is the inability of Natural Medicine Alaska, the first indigenous-led psychedelics ballot question campaign, to gain adequate funding for 2026 ballot access. Despite the Alaskan campaign having more encouraging polling than Yes on 4, donors resisted supporting the initiative, citing the recent failure in Massachusetts. According to people familiar with the fundraising operation, this appeared to have stemmed from an organized effort to convince major donors that Question 4’s defeat showed a liberal psychedelics initiative was not viable anywhere in the United States given the political climate.

An Over Two-Million-Dollar Printing Error

To get a ballot question on the ballot in Massachusetts, a campaign needs to gather tens of thousands of supportive signatures from registered voters in the state, from at least four different counties, within a strict timeframe. Consequently, ballot question campaigns like Yes on 4 typically rely on paid signature gatherers, rather than volunteers, to acquire the lion’s share of qualifying signatures.

As referenced in Part 2, a relatively minor disruption of Yes on 4’s signature gathering effort was produced by local grassroots activist James Davis, whose organization had recently received a $35,000 donation directly from the ballot committee. Davis publicized documentation of what he called “lying to voters” by signature gatherers—which was actually gatherers employing a few of the misleading, but arguably technically accurate, campaign talking points examined in Part 5. Without proof, he publicly accused signature gatherers of falsely claiming to be volunteers. And he discouraged individuals in his volunteer network from signing the ballot committee’s petitions.

A major disruption, and the focus of this subsection, was many thousands of gathered signatures being disqualified less than two weeks before the submission deadline, causing the campaign to be “at risk of missing the 2024 ballot,” according to reporting by WBUR in November 2023. The cause of the disqualifications was a union logo printed on the ballot sheets, spotted by election workers processing submitted petitions. Ballot committee spokesperson Jennifer Manley “did not respond to specific questions about the union logo or how many signatures [were] potentially at risk of being disqualified” according to WBUR, and I was never provided a detailed explanation for how the disqualifying mark was printed on numerous ballot sheets. Consequently, I am unsure to what degree the management of the ballot committee contributed to the issue.

What I was told, by Yes on 4 campaign director Jared Moffat, was the paid signature gathering company, The Outreach Team, had taken responsibility for the setback, and the setback had been a costly one, requiring many additional signatures to be gathered on an expedited basis. Moffat claimed this was reflected in the $1,744,930 “refund” the ballot committee received in installments from The Outreach Team, starting in December 2023 and ending in September 2024, in addition to a $285,070.00 in-kind contribution—$2,030,000 in total value given back to the ballot committee on account of the printing error.

These refund contributions were justified because the ballot committee had been forced to overpay upfront, paying $2,000,000 to the Outreach Team over the course of just four days in November 2023 to meet the signature gathering deadline. In total, Yes on 4 initially paid $3,275,780 to The Outreach Team to gather signatures. For comparison, the costs of paid signature gathering for other 2024 ballot question campaigns in Massachusetts were $379,838.32 for Yes on 1, $521,499 for Yes on 2, $1,639,410.93 for Yes on 3, and $740,701.97 for Yes on 5.

I can only speculate as to the full impact of the mishap, which appeared to necessitate an emergency cash infusion. On November 13, 2023, David Bronner’s company, All One God Faith, Inc., donated $1,000,000 to the ballot committee. The next day, the ballot committee paid $1,000,000 to The Outreach Team. From November 15 to November 16, 2023, the ballot committee received an additional $928,000 in monetary contributions, including $775,000 in loans. On November 17, 2023, the ballot committee paid another $1,000,000 to The Outreach Team. This sequence suggests the campaign was forced to scramble for funds to cover the upfront costs of replacement signatures.

Plausible, but unconfirmed, possible outcomes of this incident on the campaign include:

reduced donor confidence in the ballot committee, adversely affecting later fundraising;

contributions originally intended for other legitimate, time-sensitive campaign purposes being diverted to pay for rushed signature gathering, adversely affecting operations.

Undoubtedly, the incident added to the pile of negatively slanted media coverage stoked by Davis—who was quoted by WBUR as claiming grassroots activists “[were] not surprised the PAC [(New Approach)] dropped the ball with signature gathering”—and consumed substantial, nonrefundable time and energy that the campaign could have been spent elsewhere had the printing error not occurred.