“From Forest to Dust” Shows How Drug Prohibition Drives Climate Crisis

December 8, 2025

Drug prohibition is a driver of the climate crisis, outlines a major report by international researchers and policy experts. Both drug policy reform and “ecological harm reduction,” it argues, are essential to climate justice.

“From Forest to Dust: Socioeconomic and environmental impacts of the prohibition of the coca and cocaine production chain in the Amazon basin and Brazil” was produced by a coalition called Intersection – Land Use, Drug Policy and Climate Justice, involving numerous NGOs.

Its 100-plus pages cover vast historical and geographical expanses, from the Spanish colonial era to today, and from the jungles of Brazil to the ports of West Africa. It calls for a system of legal regulation for coca, but one that doesn’t simply replace the control and violence of trafficking networks with that of multinational corporations. Instead, the authors argue, Indigenous communities and family farms should be centered, to ensure that the coca and cocaine trade won’t harm people and their lands.

“When armed conflict or the military arrive, it pushes the frontier of coca production into forest-covered areas.”

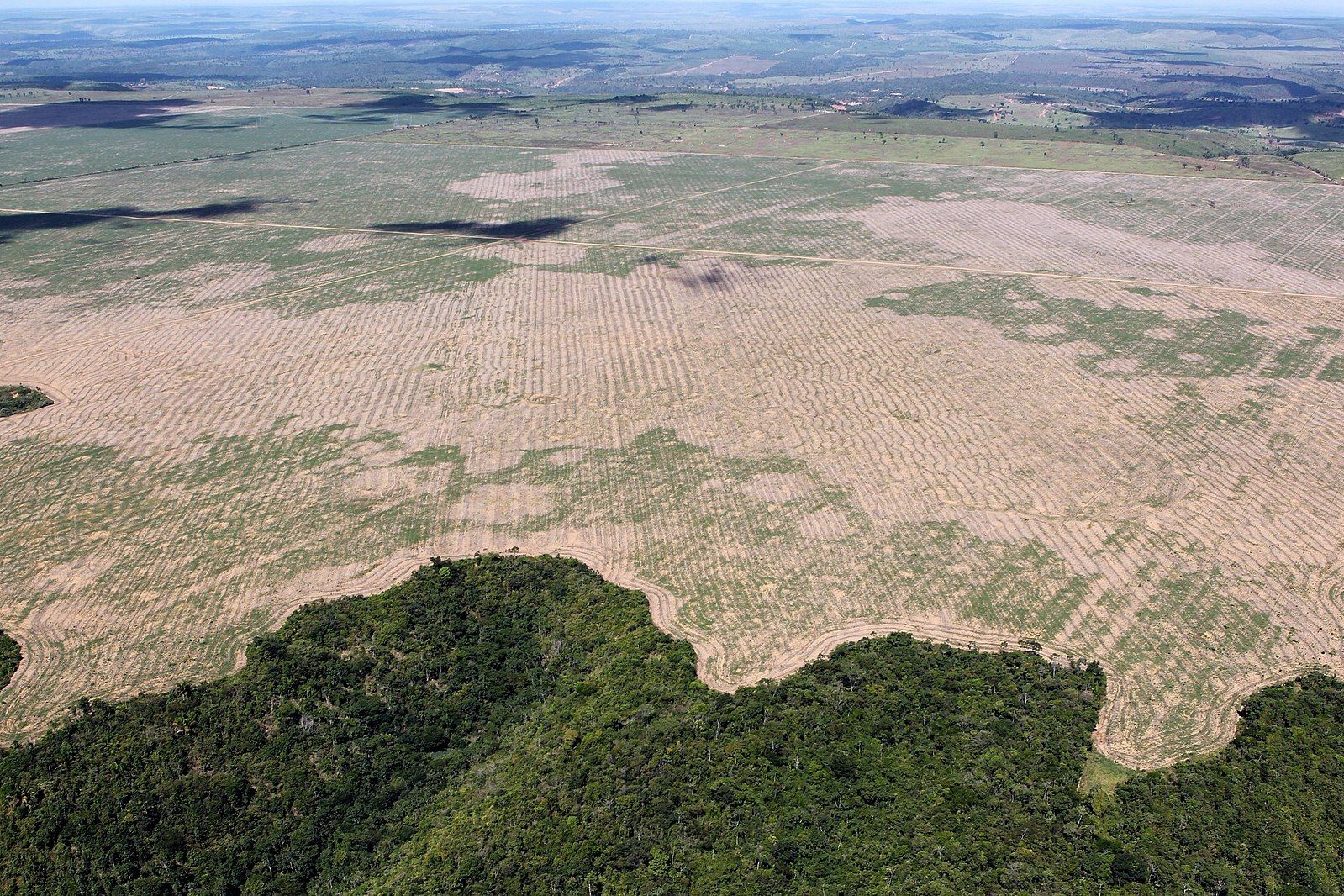

“In some regions, coca acts as a direct driver of deforestation,” Rebeca Lerer told Filter. A Brazilian journalist and human rights activist, Lerer was the editor and coordinator of the report, and founded the Intersection coalition.

“When armed conflict or the military arrive, it moves coca to more remote areas,” she explained. “It pushes the frontier of production into forest-covered areas—then authorities [seek to] eradicate coca, then usually mining or cattle ranching projects come.”

The cocaine trade is tied to environmentally destructive industries, details the report, as it provides financing and the infrastructure needed to move people, goods and services engaged in the illegal wildlife, fishing and logging trades—to name a few.

“The cocaine trade in the Amazon works as an investment bank for other environmental crime,” said Lerer, who also serves as the Latin American secretariat of the International Coalition for Drug Policy Reform and Environmental Justice, one of the groups that collaborated on the report.

“When the [authorities] repress one [cocaine trafficking] route, they shift to another forest area,” she continued. Trafficking groups “then involve traditional communities and local Indigenous lands in these routes. Repression moves this around without reducing the trade or consumption, and while increasing violence.”

The first section of the report was written by David Restrepo, research lead at the Center for Studies on Drugs and Security at the Universidad de los Andes. He gives a brief history of the coca leaf—from its ancient use as a spiritual, medicinal and communal substance in the Andes highlands; to the chemical extraction of the cocaine alkaloid and its launch as a global commodity; and finally, to the onset of prohibition and the rise of wealthy, militarized “cartels.”

“Among the millions of people across South America who continue to chew, cultivate, and revere coca, the leaf is not considered an intoxicant but a vital substance for social cohesion.”

It’s a story that’s taken another twist even since the publication of “From Forest to Dust.” On December 2, the World Health Organization opted not to recommend easing the blanket global prohibition of coca—going against the findings of the agency’s own expert report.

“Among the millions of people across South America who continue to chew, cultivate, and revere coca today, the leaf is not considered an intoxicant but a vital substance for social cohesion and balance with the natural world,” Restrepo writes.

Traditional use spans peoples like the Nasa in Colombia, mambe circles in the northwest Amazon, and Quechua-speaking highland Peru and Bolivia. But the plant’s importance to diverse cultures is overshadowed by its potent white derivative—and authorities’ disastrous attempts to suppress it.

The report covers harmful domestic and international crackdowns, the export of the United States drug war through initiatives like “Plan Colombia,” and how enforcement moves the trade around, per the “balloon effect.”

“Prohibition, even in its infancy, generated adaptive supply,” Restrepo writes. “When one route closed, another emerged.” He criticizes US and Colombia-led anti-trafficking actions, and notes how Colombia’s 2016 peace deal with the leftwing militia group FARC fragmented the cocaine trade in the country, with “dissident factions, paramilitary successors, and criminal entrepreneurs filling the authority gap.”

In Peru and Bolivia, meanwhile, Restropo explains how coca cultivation has continued to increase. Prohibition “reshuffles and disperses [the trade], often into ecologically fragile regions where state presence is weak.” He cites UNODC data showing that potential leaf yields more than doubled, from 4.1 tons per hectare in 2013 to 8.5 tons by 2023. That single hectare could produce up to 19 kilograms of cocaine per year.

Coca-related forest loss has doubled over the past decade—exceeding 20,000 hectares in some years. The refinement process also produces significant pollutants.

But changing fortunes in the global cocaine trade have made Brazil an emerging player, with groups like the Red Command and the Capital’s First Command taking key roles in manufacturing, the domestic supply and global export.

Amid these changes, coca-related forest loss has doubled over the past decade—exceeding 20,000 hectares in some years. The refinement process also produces significant pollutants from gasoline, sulfuric acid, ammonia and acetone. Field studies show elevated heavy metal and acid residues in nearby soils and waterways, and coca processing areas are associated with more fish and amphibians dying.

But efforts to eradicate coca are also environmentally destructive. Notoriously, aerial crop fumigation operations have poisoned forests, waterways, farms and human beings with the herbicide glyphosate.

The report’s second section, jointly written by University of São Paulo urban geography researcher Thiago Godoi Calil and members of the Mãe Crioula Institute, continues to document the destruction.

It describes the rise of “narco-deforestation” and “narco-mining”, where the illicit drug trade is tied to illegal extractive industries like logging, wildlife and plant smuggling, and to land-grabs and sex trafficking. The authors note that from 2017-2021, 16 major seizures in the Brazilian Amazon found cocaine shipments in illicit lumber on its way to Europe.

“Because it’s criminalized, there is no control over the waste process. It contaminates water, soil and animals … There are health hazards for lab workers.”

In the following section, members of the Instituto Fogo Cruzado cite UNODC estimates showing that global cocaine production of 3,708 tons in 2023 produced an estimated 2.19 billion tons of carbon dioxide. Every aspect of the production and supply chain—from cutting and burning forests to grow coca, to the refinement process, disposal of waste and transportation—contributes to this. And prohibition means the absence of mitigating regulations.

“The production itself generates impacts,” Lerer told Filter. “So many chemical products are used. Because it’s criminalized, there is no control over the waste process. It contaminates water, soil and animals in the surroundings. There are health hazards for lab workers, and adulterants used by people with poor expertise.”

These environmental harms go far beyond the interior regions of the Brazilian Amazon—including out to the oceans, with chemical traces found in mussels, sharks and other fish.

The multi-billion dollar cocaine industry additionally serves as an “investment bank” for extractive underground industries in Brazil, the authors write: “The main ‘indirect’ effects of the prohibition associated with this refining structure are related to the financing of other illegal activities and the use of political influence and the armed branches of the drug trade to corrupt public agents and avoid oversight. For communities and environmental defenders, this translates into an increase in deaths and threats.”

To put the scale in perspective, the authors estimate that the cocaine refinement industry alone could generate up to $6 billion a year in Brazil—a sum nearly six times larger than the total target for the Amazon Fund ($1.05 billion), a government-managed philanthropic organization combating deforestation.

In another section of the report, Mary Ryder and Steve Rolles of Transform Drug Policy Foundation briefly mention some local efforts—particularly in Europe—to consider legal regulation of cocaine and other stimulants.

Hower, they write, “More realistic in the short term, perhaps, is the possibility for coca based products, such as coca tea, coca leaf or mambe (that only contain a small amount of the active cocaine alkaloid) to be imported and sold in European markets—particularly if coca’s legal status under the UN conventions is revisited.”

“Despite these impacts, drug policy reform is almost entirely absent from the climate policy agenda.”

Jenna Rose Astwood and Clemmie James, of the International Coalition on Drug Policy Reform and Environmental Justice, conclude the report by describing an approach they call “ecological harm reduction.”

“The question is no longer why the drug war has failed—but why it persists,” they write. “The answer: it enables illegal, unregulated extraction in biodiversity-rich forests vital to our climate future.”

“Despite these impacts, drug policy reform is almost entirely absent from the climate policy agenda,” they continue. “This omission is dangerous. It is not possible to protect the Amazon, or meet climate goals, while ignoring one of the biggest forces driving its destruction.”

Astwood and James call for environmental justice and an end to the drug war, pointing to what they describe as Indigenous peoples’ “approach rooted in ecological interdependence.” But they don’t completely endorse the legal regulation of drugs unless it’s combined with efforts to protect the environment, workers and people who depend on vulnerable lands.

“A legal market, if poorly implemented, can reproduce the harms of prohibition through unsustainable agricultural practices, corporate capture, land grabbing, and further marginalization of those already embedded in the drug economy,” they write. “A just transition to a regulated drug market must reduce the influence of extractive and criminal economies by establishing safeguards to prevent exploitative actors from entering the legal space.”

“We need to start by freeing the coca leaf—from there we should design what this trade should look like from an ecological harm reduction lens.”

Their recommended components of this vision include sustainable environmental practices such as permaculture and companion planting; responsible land, water and energy use; ensuring food security for rural communities; and diversifying agricultural systems. Processing and refining of controlled substances, they argue, should be relocated to urban and suburban areas where waste can be better controlled.

They also endorse various protections for workers including the rights to organize, collective bargaining, safe working conditions, fair wages, and an end to forced and child labor. And land reforms should protect peoples with traditional ties to ecosystems. Stolen lands should be returned with just compensation, and resources should be provided for restitution and community-led redevelopment.

“Prohibition started with the plants, and we think we need to go back to the plants,” Lerer said. “We need to start by freeing the coca leaf—from there we should design what this trade should look like from an ecological harm reduction lens and avoid corporate capture. Illegal cocaine promotes environmental destruction, but ‘Big Pharma’ cocaine is also not going to deliver climate justice.”

Photograph of deforestation in northern Brazil by Felipe Werneck via Wikimedia Commons/Creative Commons 2.0

This article was originally published by Filter, an online magazine covering drug use, drug policy and human rights through a harm reduction lens. Follow Filter on Bluesky, X or Facebook, and sign up for its newsletter.