2025: The Year of Ibogaine Therapy

By Noah Daly

On the second day of the Psychedelic Science 2025 conference in Denver, CO in June, a crowd of roughly two hundred people filed into the Bluebird Ballroom to hear former Texas governor Rick Perry–a staunch conservative from a state known for being tough on drug users– offer his opening remarks about ibogaine, the psychedelic drug he believes can change the course of American medicine. With more than 400 sessions and events over three days, there were many rabbit holes to dive into at the largest gathering of the world’s psychedelic communities. This year, ibogaine, a compound derived from a family of shrubs found mainly in Gabon and neighboring nations of Western Africa, held a place of heightened interest.

“I became a complete believer in this,” Perry told the audience. “One of my political consultants called me and said, ‘you’re about to throw 40 years of conservative policy out the window on this hippie shit.’” Perry, a former United States Air Force pilot, recalled the long talks he’d had with veterans in Texas who’d struggled for years with mental health issues after coming home from combat, only to find unparalleled relief in ibogaine therapy. He reflected that his career in politics was rooted in the Air Force’s zero-tolerance policy for drugs, “but my reputation is not worth more than [veterans’] lives.”

Veterans and their supporters made up perhaps the single largest cohort of attendees at Psychedelic Science this year; they even got their own stage. On June 11th, less than a week before the conference began, Texas Governor Greg Abbot signed into law a bill that committed $50 million of the state’s budget to researching ibogaine. The effort to bring that bill to life was championed by a coalition of advocates, including Perry, who gave his remarks to open a series of sessions on Thursday dedicated to a modern and increasingly global approach to ibogaine’s therapeutic potential.

Ibogaine Comes to America

Like many of the traditionally used plant medicines discussed at the conference, advocates believe that the iboga plants cultivated in Central Africa and the ibogaine used in the West are at risk from corporatization and predatory practices that separate these powerful medicines from the people who’ve stewarded them for hundreds if not thousands of years. NGOs focused on protecting Gabonese rights regarding the global proliferation of iboga and ibogaine were on hand in Denver, giving stark warnings about what they see just behind the hype surrounding one of the most potent and long-lasting psychoactive compounds.

Iboga has been used as part of a coming of age ritual and as medicine by several groups who follow the religious philosophies of Bwiti for centuries. Originally developed by the Bobongo pygmy tribes native to Gabon, Bantu peoples who migrated to the region learned to give preparations of the iboga root bark to treat a range of ailments. They eventually developed coming-of-age rituals around the intense, days-long psychoactive journey the plant medicine creates. When iboga’s medicinal use was discovered by French colonists, its extract was sold as a mental and physical stimulant beginning in the 1930s for several decades in France, before making it to the United States in the 1960s.

After an New York University undergraduate, Howard Lotsof found that ingesting ibogaine cured him of his heroin addiction, and it became known as an underground miracle cure for substance use disorder. In the last ten years, ibogaine has experienced a surge of new interest as a breakthrough for treating veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and traumatic brain injury. In the last five years, thousands of American veterans have traveled outside the U.S. to receive ibogaine in Westernized health clinics.

Perry’s rallying cry for the American ibogaine movement was followed by a talk by Dr. Nolan Williams of Stanford University, who offered sobering insights into the glacial pace of scientific change. Williams joined the psychedelic research scene just three years ago when it was announced that he was finalizing a now-famous study of 31 special operations forces veterans who received ibogaine therapy for PTSD. That study, published in Nature Medicine in January of 2024, is cited as the launching point for the current wave of interest in using ibogaine to treat PTSD, traumatic brain injuries, and central nervous system disorders.

The precedent for the West’s skepticism of plant medicines is a longstanding one. Williams offered the story of James Lind, a Scottish naval surgeon who conducted the world’s first clinical trial in 1747. Lind treated a group of sailors afflicted by scurvy with citrus fruits or arsenic (today a widely recognized poison) to see which was the more effective intervention. “We knew in 1499 John Woodall wrote that you could take citrus fruit for scurvy and solve it,” Williams says, “but the problem is that institutions do not like these sorts of ideas, and they then reject those ideas. Then it’s only through science that you can have this rediscovery and eventual acceptance.”

After Lind’s study, it took another 100 years before this became implemented. Williams points out that between 1500 and 1800, some two million people died of scurvy, as many as those who died in combat during the Korean War, “because science wasn’t translated into policy.”

“The real issue that I want to bring up with plant medicines and the way that humans think about solving problems from the hubristic lens of science and medicine is that there’s an initial discovery … I would argue that there’s a long history of medicine where we may solve huge health crises before we understand how it works.”

Safety Concerns Underpin Optimism For Effective Ibogaine Therapies

A key consideration highlighted by Williams and others is the question of safety. Ibogaine has a well-known transient cardiotoxicity, and is capable of causing heart failure. Patients must be thoroughly screened, counseled, and supervised with extreme care. “The publicity and policies are very exciting on one hand,” said panelist Juliana Mulligan, a social worker and expert in the safe use of ibogaine, “but we don’t need more clinics. Like, don’t invest in a new clinic. Please invest in building training and accountability programming so that we can make what we have safer… I don’t really feel that we were prepared and ready for [the publicity and new policies around ibogaine] to happen yet.”

One of the attendees in the audience for Mulligan’s remarks was Marissa Hardy, a graduate student of transpersonal psychology and an initiate in the Missoko Bwiti tradition, one of the five principal Gabonese groups stewarding the traditional use of iboga. Hardy herself has experienced full plant iboga ceremonies and Western ibogaine experiences, and shares the concerns expressed by Mulligan and others.

“Six years ago, I had issues with practitioners not having a good enough integration process. Integration is everything in traditional medicine. Traditional use of this integration process is anywhere from 12 to 18 months, and when I was looking at facilities online, their integration process was only two weeks, which I thought was incredibly concerning, considering that people can revert back into their old habits or addictions 10 times worse.”

Hardy, who says she has supported more than 100 individuals going through iboga and ibogaine ceremonies, was reassured by what she heard during a closed workshop on ibogaine at the conference. The workshop, entitled Ibogaine Treatment: Therapeutic Targets, Efficacy, Subjective Effects, and Post-Treatment Integration, was co-led by two founders of the Ambio Life Sciences clinic, anthropologist Tom Kingsley Brown, and Beth Sparks, an integration coach and therapist who spoke at length about her approach to extended post-treatment care of patients undergoing ibogaine therapy.

“Hearing Beth talk about how she follows up and that they have the weekly calls and all these things for a year or more in some cases gave me a lot of confidence that this medicine could actually get past the FDA one day. There’s a lot we can learn from that approach.”

There has never been an official training process to work with Ibogaine, which according to Mulligan is the most dangerous psychedelic. As the drug is being launched on a global scale, experts like Mulligan are calling for more comprehensive training protocols and oversight of those providing ibogaine in a therapeutic setting, not more ibogaine clinics. “While there are practitioners who work with ibogaine safely, the majority do not. That’s not just a medical lack of safety, but also a lack of understanding of what trauma-informed care and ethical care are.”

The Road Beyond The Lone Star State

The news about the Texas ibogaine funding was a cause for celebration at the Psychedelic Science conference. The Texas ibogaine initiative may offer hope for a growing number of Americans desperate for alternatives to traditional interventions for conditions such as substance use disorder, traumatic brain injury, and major depressive disorder. Shortly after Psychedelic Science, the state legislature in Arizona passed a bill that amends the state budget for the fiscal year 2026 to include a $5 million dollar commitment to funding a clinical trial of ibogaine. Those funds are expected to be matched by unspecified private sector donors, making for a total $10 million dollar investment. These early commitments from predominantly conservative states mark a much larger national interest in ibogaine, but some experts in indigenous use and harm reduction say there’s much more work ahead.

When Williams shifted gears in his talk, he made a point to acknowledge the people of Gabon practicing Bwiti traditions, as other speakers on ibogaine did during the conference. “The West can’t discover things it can’t see,” Williams told the audience. “The West has no reason to look at something if it can’t, at least, see the indigenous peoples first.”

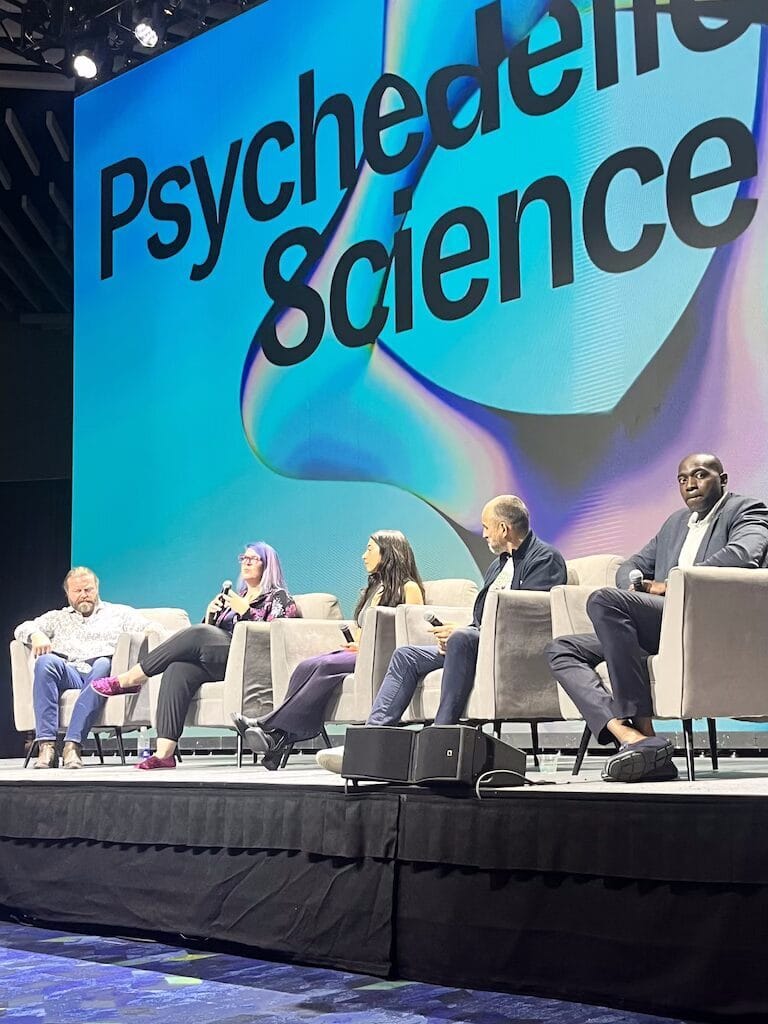

A panel discussion, Ibogaine and Iboga: Healing, Responsibility, and the Big Picture. From left to right: Bryan Hubbard, Lynette Averill, Julianna Mulligan, Yann Guignon, and Stéphane Lasme.

Several panel discussions at the conference included numerous Western medical doctors and researchers who had spent years working with Gabonese shamans practicing Bwiti and using iboga, but there were relatively few voices from Gabon itself. David Nassim, co-director of Blessings of the Forest — an NGO focused on the sustainable and equitable growth of iboga and ibogaine for indigenous Gabonese communities —was pleased to hear those on stage acknowledge the cultural roots of iboga and ibogaine.

“[The Texas Initiative] was launched in the context of America, which comes first, and the context of Gabon, which comes second, so there isn’t prior and informed consent,” Nassim says. He feels that, while it is good that Texans are charging ahead with their commitment to research, advocacy groups like Blessings of the Forest need to do work with people “who are open and have a very big heart for including indigenous voices.”

“People like Bryan Hubbard,[Executive Director of Americans for Ibogaine], who’s publicly acknowledged the elders here at least twice. [Hubbard is] doing whatever he can because he knows that that’s a freight train and it’s left the station.”

Nassim and other advocates for Gabonese communities, whom Lucid News spoke to at Psychedelic Science, believe that, while the victory in Texas is a meaningful acceptance of healing traditions from Gabon to the U.S., even greater progress is on the horizon. Since the conference, Hubbard has spoken on the podcasts of MAGA-friendly comedian Theo Von and former House Speaker Newt Gingrich.

Nassim pointed to the progress made locally in the Rocky Mountains. “Lorey Bratton has got a chance to do something great with the Colorado Natural Medicine Program because their policy indicates that the whole of that plant medicine has to be used, and that indigenous people have to be engaged with from the beginning, and other states may pick up on that,” said Nassim.

The program seeks to address the state’s mental health and addiction crisis, allowing adults 21 and over to access psychedelic-assisted care without needing a formal diagnosis. The therapy follows a structured four-step process—screening, preparation, administration, and integration—guided by trained facilitators and delivered at licensed healing centers or in the offices of facilitators.

While these initiatives continue, the state‑mandated Indigenous advisory group in Colorado has called on officials to pause the rollout of regulated psilocybin therapy and delay similar programs involving mescaline, ibogaine, and DMT until June 1, 2026. As Westworld first reported, while Psychedelic Science 2025 was still underway, the pause was suggested to better address cultural protections and ensure equitable access.

The indigenous working group was established as part of the implementation of Proposition 122 decriminalization legislation and has raised concerns about how current regulations may overlook Indigenous perspectives and could lead to harm or exclusion. The group’s recommendations highlight a tension between the state’s broader movement toward therapeutic psychedelics and the call for greater deference to tribal sovereignty and traditional medicine practices.

From July 3 through the 5th, just weeks after the Denver conference, Yann Guignon (third from the left) presented his experience at Psychedelic Science to the congregation of Bwiti practioning tribes.

Who Speaks for Gabon?

During one panel at the conference entitled “Indigenous-Led Biocultural Conservation Success Stories with Ayahuasca, Iboga, and Peyote,” indigenous Colombian lawyer Patricia Tobón pointed out that many of the groups using ayahuasca she’s represented have fallen victim to complex bureaucracies far removed from the communities where they live and operate. “We as indigenous people have to deal with so many violences at the same time, and then dealing with this huge monster without having the resources… we’re in a state of enormous vulnerability.”

“The connection that we have with [plant] medicine in Gabon is different from what we are hearing from other parts of the world,” says Georges Gassita, an environmental lawyer for Blessings of the Forest… It has not been criminalized.” Gassita said. “Indigenous communities in Gabon are aware of the interest in the therapeutic capacities of this plant, but the concern is that if Gabon can heal humanity through iboga, it has to be done with respect for the fundamental rights of the indigenous nations.”

Bringing the Gabonese communities together to address the recent global interest in their heritage has been a main focus and an extraordinary challenge for Blessings of the Forest, according to Yann Guignon, a founding member of the organization. Guignon spoke on several panels throughout the conference, including one alongside Mulligan, Hubbard, Dr. Lynette Averill of the Baylor College of Medicine, and Gabonese-American businessman Stéphane Lasme in a panel entitled Ibogaine and Iboga: Healing, Responsibility, and the Big Picture.

Gabonese-American businessman Stéphane Lasme addressing the panel on-screen.

“There are 56 different ethnic groups in Gabon, five different groups practicing different forms of Bwiti…” said Guignon. He said the challenge has been “to convince all branches [of Bwiti] to come together and become a main voice. But we’ve had to approach them slowly to earn trust and try to understand if they want to be in the discussion.”

Guignon, who’s been a Gabonese citizen for several decades and has been adopted into a Gabonese family, described the process of gathering the various branches of Bwiti-practicing groups within Gabon to create a coalition. “…first villages by villages, then province by province, then national association. We succeeded today. And after this conference, there’s a national conference in Gabon that gathers all those peaceful people, and I have to make a brief to them about what’s going on here, in front of them and in front of politicians, as we were invited to this conference.”

Just two weeks after the Psychedelic Science conference , from July 3rd to July 5th, the Maghanga Ma Nzambe Council, the organization of Bwiti lineage holders that Guignon spoke about assembling, held their first-ever national conference in Gabon..

Hubbard, who mediated the panel, raised two concerns: a recognition of the rich history of smash-and-grab business models in American history, and simultaneous concerns about the capacity, honesty, and legitimacy of those who assert themselves as intermediaries between the West and Africa. In a group of notably outspoken experts, the relative unknown to the audience, Lasme, gave the pin-drop soundbite on the panel.

“The first thing that we have to understand–and this is that there is no one here currently in this facility who represents [Gabon], right? I don’t represent Gabon. I’m an entrepreneur trying to build something, and the effect could change in a way I only know. He [pointing to Guignon] does it in a way he only knows, but he does not speak – with all the respect in the world, Maghanga Ma Nzambe does not represent Gabon.”

Lasme, a venture capitalist and cannabis investor, emphasized the importance of recognizing and working with the Central African nation at various levels. “People who represent Gabon, technically, are the government. So if a conversation needs to happen, the government has to speak. If a conversation has to happen in terms of exchange of technology, business people have to speak. In terms of affecting people’s lives and changing them, that’s the NGO conversation. We all have our aims…”

“The smash-and-grab mentality is real. It’s been happening in Africa forever, and African people know about it,” Lasme reminded the audience.” [If we want to include Gabonese people] Let’s invite them here, let them speak on stage… we have translators– come on people, it’s 2025. So let’s stop the excuses of how difficult it is, let’s just do it.”